____________________________________________________________________________

21° Bisabuelo/ Great Grandfather de: Carlos Juan Felipe Antonio Vicente De La Cruz Urdaneta Alamo →Íñigo (Enneco ) Arista de Pamplona, 1st King of Pamplona is your 21st great grandfather.

____________________________________________________________________________

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

(Linea Materna)

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Íñigo (Enneco ) Arista de Pamplona, 1st King of Pamplona is your 21st great grandfather.of→ Carlos Juan Felipe Antonio Vicente De La Cruz Urdaneta Alamo→ Morella Álamo Borges

your mother → Belén Borges Ustáriz

her mother → Belén de Jesús Ustáriz Lecuna

her mother → Miguel María Ramón de Jesus Uztáriz y Monserrate

her father → María de Guía de Jesús de Monserrate é Ibarra

his mother → Teniente Coronel Manuel José de Monserrate y Urbina

her father → Antonieta Felicita Javiera Ignacia de Urbina y Hurtado de Mendoza

his mother → Andrés Manuel Ortiz de Urbina y Landaeta, I Marqués de Torrecasa

her father → Manuel Ortiz de Urbina y Márquez de Cañizares

his father → Manuel de Ortiz de Urbina y Suárez

his father → Juan Ortíz de Urbina y Eguíluz

his father → Martín Ortíz de Urbina

his father → Pedro Ortiz de Urbina

his father → Ortún Díaz de Urbina

his father → Diego López

his father → María Sánchez Ordóñez de Lemos, princesa de León

his mother → Sancho Sánchez, señor de Erro

her father → Andregoto Gómez

his mother → Velasquita Galíndez

her mother → Galindo II Aznárez de Aragón, conde de Aragón

her father → Oneca (Iñiga) García de Pamplona

his mother → García I Íñiguez, rey de Pamplona

her father → Íñigo (Enneco ) Arista de Pamplona, 1st King of Pamplona

his fatherConsistency CheckShow short path | Share this path

You might be connected in other ways.

Show Me

Íñigo (Enneco ) Arista de Pamplona, 1st King of Pamplona MP

Portuguese: Íñigo Arista de Pamplona, 1st King of Pamplona, Arabic: بن فورتون, 1st King of Pamplona

Gender: Male

Birth: 790

Bigorra, País Vasco, España (Spain)

Death: 851 (60-61)

Pamplona, Navarra, España (Spain)

Place of Burial: Monasterio de San Salvador de Leyre, Camino de Santiago, Yesa, Navarra, España (Spain)

Immediate Family:

Son of Íñigo Jiménez, de Pamplona and Oneca بن فورتون

Husband of Oneca Velázquez

Father of Assona ibn Musa al Qasaw; Nunila Iñiguez de Pamplona; García I Íñiguez, rey de Pamplona and Galindo Iñíguez de Pamplona

Brother of Fortún Iñiguez de Pamplona

Half brother of Musa Ibn Musa o Muza Ibn Muza o "Musa (Fortún) lbn Qasaw, Walí de Tudela y Huesca y Zaragoza"; Mutarrif ibn Musa, valí de Huesca; Jonás (Yunus) ibn Musa; Yuwartas ibn Musa; Lupo (Lubb) ibn Musa and 2 others

Added by: Alvaro Enrique Betancourt on June 16, 2007

Managed by: Ric Dickinson and 107 others

Curated by: Luis Enrique Echeverría Domínguez, Curator

0 Matches

Research this Person

3 Inconsistencies

Contact Profile Managers

View Tree

Edit Profile

Overview

Media (27)

Timeline

Discussions

Sources

Revisions

DNA

About

English (default) history

Íñigo Íñiguez, Enneco Enneconis (en latín) o Eneko Aritza (en euskera) (c. 770 — 851) primer rey de Pamplona entre los años 810/820 y 851, conde de Bigorra y rey de Sobrarbe. Se le considera patriarca de la dinastía Íñiga, que sería la primera dinastía real pamplonesa.

Hijo de Íñigo Fortún y Oneca, La Íñiga o Eneconis, fundadora de la Casa Real de Pamplona-Navarra, proviene de una línea distinta a la dinastía Jimena, siendo ambas de raíz de extracciones muy diferentes, aunque muy emparentadas entre sí. Una es reconocidamente visigoda, proveniente de un Eneco, Conde de Calahorra, muy vinculada a la de Fortún, Conde de Borja, y la otra aquitano-cantabrica, descendiente directa del gran Duque Eudon de Aquitania (a través de la línea Lope-Alarico-Seimino o Jimeno) tal como lo establecen importantes trabajos realizados al respecto. La confusión se debe a la aparición tardíamente de un Íñigo Jiménez, hermano del co-regente García Jiménez e hijos ambos de Seimino, contemporáneos del rey García I Íñiguez y confundidos en nombres y en cronología.

Muerto su padre, su madre se casó en segundas nupcias con el Banu Qasi Musa ibn Fortún de Tudela, uno de los señores del valle del Ebro, con cuyo apoyo llegó al trono, y que fueron los padres de Musa ibn Musa. Este matrimonio dejó bajo la influencia de Íñigo Arista unos territorios considerables: desde Pamplona hasta los altos valles pirenaicos de Irati (Navarra) y Valle de Hecho (Aragón). Los Banu Qasi controlaban las fértiles riberas del Ebro, desde Tafalla hasta las cercanías de Zaragoza.

El advenimiento del primer rey de Pamplona no se hizo sin dificultades. Entre los núcleos de población cristiana (minoritaria), algunos dan su apoyo al partido franco, sostenido primero por Carlomagno y más tarde por Luis el Piadoso. La rica familia cristiana de los Velasco está a la cabeza de ese partido.

En 799, unos procarolingios asesinan al gobernador de Pamplona, pariente de Íñigo Arista, Mutarrif ibn Muza, bisnieto del conde Casio. En 806, los francos controlan Navarra a través de un Velasco como gobernador. En 812, Luis el Piadoso manda una expedición contra Pamplona. El regreso no es muy glorioso, tomando como rehenes a niños y mujeres de la zona para protegerse durante el paso del puerto de Roncesvalles.

En 824 los condes francos Elbe y Aznar dirigen otra expedición contra Pamplona, pero son vencidos por Íñigo con el apoyo de sus yernos Musa ibn Musa y García el Malo de Jaca. Íñigo Arista es nombrado por trescientos caballeros rey, en la Peña de Oroel, Jaca.

Entonces aparece Íñigo Arista como princeps: "Christicolae princeps" (príncipe cristiano), según Eulogio de Córdoba.

Fruto de esta alianza fue la intervención en las luchas de los Banu Quasi con los Omeyas de Córdoba, lo que motivó las represalias de Abderramán II contra Pamplona.

En 841 es víctima de una enfermedad que lo deja paralítico. Su hijo García Íñiguez ejerce una fuerte regencia, llevando la dirección de las campañas militares. Pero la política de alianzas continúa. Así, su hija Assona se casa con su tío Musa ibn Musa.

Descendencia[editar •(Según Lévi-Provençal, pudo ser polígamo, igual que sus parientes los Banu Qasi.

Fue padre de:

Assona Íñiguez, casada en 820 con Musa ibn Musa, valí de Tudela y Huesca, su medio-tío al ser hermano uterino de su padre Íñigo Arista. García Íñiguez, sucesor en el trono, quien ejerció la regencia cuando su padre quedó paralítico. Galindo Íñiguez de Pamplona, asesinado en 843, fue padre de Musa ibn Galindo, valí de Huesca en 860 y asesinado en 870 en Córdoba. Una hija de nombre desconocido casada con el conde García “el Malo” de Aragón.

https://www.geneaordonez.es/datos/getperson.php?personID=I46207&tree=MiArbol

==========================

II - ÍÑIGO ARISTA "el Vascón". (Eneko Aritza)

Nacido ~781, fallecido en 852. Conde de Bigorre y de Sobrarbe, I Rey de Pamplona 822. Casó con:

ONECA VELÁZQUEZ, hija de Velasco, Señor de Pamplona; fallecido en 816. Padres de:

1.- Assona Íñiguez, casó con Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún, Walí de Tudela y Huesca. C/s.

2.- García I Íñiguez, sigue la línea.

3.- Galindo Íñiguez de Pamplona, fallecido en 851 en Córdoba. Padre de:

A.- Musa Ibn Galindo, Walí de Huesca 860, asesinado en 870 en Córdoba.

4.- Nunila, casó con el Conde García “el Malo” de Aragón.II - ÍÑIGO ARISTA "el Vascón". (Eneko Aritza)

Nacido ~781, fallecido en 852. Conde de Bigorre y de Sobrarbe, I Rey de Pamplona 822. Casó con:

ONECA VELÁZQUEZ, hija de Velasco, Señor de Pamplona; fallecido en 816. Padres de:

1.- Assona Íñiguez, casó con Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún, Walí de Tudela y Huesca. C/s.

2.- García I Íñiguez, sigue la línea.

3.- Galindo Íñiguez de Pamplona, fallecido en 851 en Córdoba. Padre de:

A.- Musa Ibn Galindo, Walí de Huesca 860, asesinado en 870 en Córdoba.

4.- Nunila, casó con el Conde García “el Malo” de Aragón.

Assona Íñiguez, who married her father's half-brother, Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortun ibn Qasi, lord of Tudela and Huesca

García Íñiguez, regent and then Íñigo's successor as 'king'.

Galindo Íñiguez, fled to Córdoba where he was friend of Eulogius of Córdoba. The Musa ibn Galind, Amil of Huesca in 860, assassinated in 870, was apparently his son.[13]

a daughter who married Count García el Malo (the Mean) of Aragón.[9]

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%8D%C3%B1igo_Arista

http://www.friesian.com/perifran.htm#basque

http://genealogics.org/getperson.php?personID=I00106660&tree=LEO

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%8D%C3%B1igo_Arista_de_Pamplona Íñigo Íñiguez, más conocido como Íñigo Arista, García Jiménez, Enneco Enneconis o Eneko Aritza (c. 781 — 852), primer rey de Pamplona entre los años 810/820 y 852, Conde de Bigorra y de Sobrarbe. Se le considera patriarca de la dinastía Íñiga que sería la primera dinastía real de Pamplona.

Hijo de Íñigo Jiménez y Oneca. Muerto su padre, su madre se casó en segundas nupcias con el Banu Qasi Musá ibn Fortún de Tudela, uno de los señores del valle del Ebro, con cuyo apoyo llegó al trono. Este matrimonio dejó bajo la influencia de Íñigo Arista unos territorios considerables: desde Pamplona hasta los altos valles pirenáicos de Irati (Navarra), y Valle de Hecho (Aragón). Los Banu Qasi controlan las fértiles riberas del Ebro, desde Tafalla hasta las cercanías de Zaragoza.

El advenimiento del primer rey de Navarra no se hizo sin dificultades. Entre los núcleos de población cristiana (minoritaria), algunos dan su apoyo al partido franco, sostenido primero por Carlomagno, y más tarde por Luis el Piadoso. La rica familia cristiana de los Velasco está a la cabeza de ese partido.

En 799, unos procarolingios asesinan al gobernador de Pamplona Mutarrif ibn Muza, de la familia de los Banu Qasi. En 806, los francos controlan Navarra a través de un Velasco como gobernador. En 812, Luis el Piadoso manda una expedición contra Pamplona. El regreso no es muy glorioso, tomando como rehenes a niños y mujeres de la zona para protegerse durante el paso de los puertos de Roncesvalles.

En 824 los condes francos Elbe y Aznar dirigen otra expedición contra Pamplona, pero son vencidos por Íñigo con el apoyo de sus yernos Musá ibn Fortún y García el Malo de Jaca.

Entonces aparece Íñigo Arista como rey de Pamplona: "Christicolae princeps" (príncipe cristiano), según Eulogio de Córdoba.

El reino de Pamplona (más tarde de Navarra) nació, pues, de la alianza firme entre los musulmanes y los cristianos. Fruto de esta alianza fue la intervención en las luchas de los Banu Quasi con los Omeyas de Córdoba, lo que motivó las represalias de Abd al-Rahman II contra Pamplona.

En 841 es víctima de una enfermedad que lo deja paralítico. Su hijo García Íñiguez ejerce una fuerte regencia, llevando la dirección de las campañas militares. Pero la política de alianzas continúa. Así, su hija Assona se casa con Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún.

Descendencia Se casó con Oneca Velázquez, hija de Velasco, Señor de Pamplona, fallecido en 816.

Hijos:

Assona Íñiguez, casada con Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún, Walí de Tudela y Huesca. García Íñiguez, sucesor en el trono (ANCESTRO). Galindo Íñiguez de Pamplona, fallecido en 851 en Córdoba. Padre de: Musa Ibn Galindo, Walí de Huesca 860, asesinado en 870 en Córdoba. Nunila, casada con el Conde García “el Malo” de Aragón.

Íñigo Arista of Pamplona From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Íñigo Íñiguez Arista (Arabic: ونقه بن ونقه, Wannaqo ibn Wannaqo, Basque: Eneko Enekones Aritza/Haritza/Aiza) (c. 790 – 851 or 852) was the first King of Pamplona (c. 824 – 851 or 852). He is said by a later chronicler to have been count of Bigorre, or at least to have come from there, but there is no near-contemporary evidence of this.[1] His origin is obscure, but his patronymic indicates that he was the son of an Íñigo.[2] It has been speculated that he was kinsman of García Jiménez, who in the late 8th century succeeded his father Jimeno 'the Strong' in resisting Carolingian expansion into Vasconia. He is also speculated to have been related to the other Navarrese dynasty, the Jiménez.[3] His mother also married Musa ibn Fortun ibn Qasi, by whom she was mother of Musa ibn Musa ibn Qasi, head of the Banu Qasi and Moslem ruler of Tudela, one of the chief lords of Valley of the Ebro.[4] Due to this relationship, Íñigo and his kin frequently acted in alliance with Musa ibn Musa and this relationship allowed Íñigo to extend his influence over large territories in the Pyrenean valleys. The family came to power through struggles with Frankish and Muslim influence in Spain. In 799, pro-Frankish assassins murdered Mutarrif ibn Musa, governor of Pamplona, the brother of Musa ibn Musa ibn Qasi and perhaps of Íñigo himself. In 820, Íñigo intervened in the County of Aragon, ejecting a Frankish vassal, count Aznar I Galíndez, in favor of García el Malo (the Bad), who would become Íñigo's son-in-law. In 824, the Frankish counts Aeblus and Aznar Sánchez made an expedition against Pamplona, but were defeated in the third Battle of Roncesvalles. The Basque victors are not named, but it was in the context of this defeat that Íñigo is said to have been pronounced "King of Pamplona" in that city by the people. Íñigo was a Christicolae princeps (Christian prince), according to Eulogio de Córdoba.[citation needed] However, his kingdom continually played Moslem and Christian against themselves and each other to maintain independence against outside powers. In 840 his lands were attacked by Abd Allah ibn Kulayb, wali of Zaragoza, leading his half-brother, Musa ibn Musa into rebellion.[5] The next year, Íñigo fell victim to paralysis in battle against the Norse with Musa ibn Musa.[citation needed] His son García acted as regent, in concert with Fortún Íñiguez (Arabic: فرتون بن ونقه, Fortūn ibn Wannaqo), "the premier knight of the realm", the king's brother and also half-brother of Musa. They joined Musa ibn Musa in an uprising against the Caliphate of Córdoba. Abd-ar-Rahman II, emir of Córdoba, launched reprisal campaigns in the succeeding years. In 843, Fortún Íñiguez was killed, and Musa unhorsed and forced to escape on foot, while Íñigo and his son Galindo escaped with wounds and several nobleman, most notably Velasco Garcés defected to Abd-ar-Rahman. The next year, Íñigo's own son, Galindo Íñiguez and Musa's son Lubb ibn Musa went over to Córdoba, and Musa was forced to submit. Following a brief campaign the next year, 845, a general peace was achieved.[6] In 850, Mūsā again rose in open rebellion, supported again by Pamplona,[7] and envoys of Induo (thought to be Íñigo) and Mitio,[8] "Dukes of the Navarrese", were received at the French court. Íñigo died in the Muslim year 237, which is late 851 or early 852, and was succeeded by García Íñiguez.[9] The name of the wife (or wives) of Íñigo is not reported in contemporary records, although chronicles from centuries later assign her the name of Toda or Oneca.[10] There is also scholarly debate regarding her derivation, some hypothesizing that she was daughter of Velasco, lord of Pamplona (killed 816), and others making her kinswoman of Aznar I Galíndez[11]. He was father of the following known children:[12] Assona Íñiguez, who married her father's half-brother, Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortun ibn Qasi, lord of Tudela and Huesca García Íñiguez, the future king Galindo Íñiguez, fled to Córdoba where he was friend of Eulogio of Córdoba and became father of Musa ibn Galindo, Wali of Huesca in 860, assassinated in 870 in Córdoba [13] a daughter, wife of Count García el Malo (the Bad) of Aragón. The dynasty founded by Íñigo reigned for about 80 years, being supplanted by a rival dynasty in 905. However, due to intermarriages, subsequent kings of Navarre descend from Íñigo. [edit]References

[edit]Sources Barrau-Dihigo, Lucien. Les origines du royaume de Navarre d'apres une théorie récente. Revue Hispanique. 7: 141-222 (1900). de la Granja, Fernando. "La Marca Superior en la obra de Al-'Udri". Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragon. 8:447-545 (1967). Lacarra de Miguel, José María. "Textos navarros del Códice de Roda". Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragon. 1:194-283 (1945). Lévi-Provençal, Evariste. "Du nouveau sur le Royaume de Pampelune au IXe Siècle". Bulletin Hispanique. 55:5-22 (1953). Lévi-Provençal, Evariste and Emilio García Gómez. "Textos inéditos del Muqtabis de Ibn Hayyan sobre los orígines del Reino de Pamplona". Al-Andalus. 19:295-315 (1954). Mello Vaz de São Payo, Luiz. "A Ascendência de D. Afonso Henriques". Raízes & Memórias 6:23-57 (1990). Pérez de Urbel, Justo. "Lo viejo y lo nuevo sobre el origin del Reino de Pamplona". Al-Andalus. 19:1-42 (1954). Sánchez Albernoz, Claudio. "La Epistola de S. Eulogio y el Muqtabis de Ibn Hayan". Princípe de Viana. 19:265-66 (1958). Sánchez Albernoz, Claudio. "Problemas de la historia Navarra del siglo IX". Princípe de Viana, 20:5-62 (1959). Settipani, Christian. La Noblesse du Midi Carolingien, Occasional Publiucations of the Unit for Prosopographical Research, Vol. 5. (2004). Stasser, Thierry. "Consanguinity et Alliances Dynastiques en Espagne au Haut Moyen Age: La Politique Matrimoniale de la Reinne Tota de Navarre". Hidalguia. No. 277: 811-39 (1999).

Íñigo Íñiguez Arista (c. 790 – 851 or 852) was the first King of Pamplona (c. 824 – 851 or 852). He is said by a later chronicler to have been count of Bigorre, or at least to have come from there, but there is no near-contemporary evidence of this. His origin is obscure, but his patronymic indicates that he was the son of an Íñigo. It has been speculated that he was kinsman of García Jiménez, who in the late 8th century succeeded his father Jimeno in resisting Carolingian expansion into Vasconia. He is also speculated to have been related to the other Navarrese dynasty, the Jiménez.

His mother also married Mūsā ibn Fortún ibn Qasi, by whom she was mother of Mūsā ibn Mūsā ibn Qasi, head of the Banu Qasi and Moslem king of Tudela, one of the chief lords of Valley of the Ebro. Due to this relationship, Íñigo and his kin frequently acted in alliance with Mūsā ibn Mūsā and this relationship allowed Eneko to extend his influence over large territories in the Pyrenean valleys.

The family came to power through struggles with Frankish and Muslim influence in Spain. In 799, pro-Frankish assassins murdered Mutarrif ibn Mūsā, governor of Pamplona, the brother of Mūsā ibn Mūsā ibn Qasi and perhaps of Íñigo himself. In 820, Íñigo intervened in the County of Aragon, ejecting a Frankish vassal, count Aznar I Galíndez, in favor of García el Malo (the Bad, who would become Íñigo's son-in-law. In 824, the Frankish counts Aeblus and Aznar Sánchez made an expedition against Pamplona, but were defeated in the third Battle of Roncesvalles. The Basque victors are not named, but it was in the context of this defeat that Íñigo is said to have been pronounced "King of Pamplona" in that city by the people. Íñigo was a Christicolae princeps (Christian prince), according to Eulogio de Córdoba. However, his kingdom continually played Moslem and Christian against themselves and each other to maintain independence against outside powers.

In 840 his lands were attacked by Abd Allah ibn Kulayb, wali of Zaragoza, leading his half-brother, Mūsā ibn Mūsā into rebellion. The next year, Eneko fell victim to paralysis in battle against the Norse with Mūsā ibn Mūsā. His son García acted as regent, in concert with Fortún Íñiguez, "the premier knight of the realm", the king's brother and also half-brother of Mūsā. They joined Mūsā ibn Mūsā in an uprising against the Caliphate of Córdoba. Abd-ar-Rahman II, emir of Córdoba, launched reprisal campaigns in the succeeding years. In 843, Fortún Íñiguez was killed, and Mūsā unhorsed and forced to escape on foot, while Eneko and his son Galindo escaped with wounds and several nobleman, most notably Velasco Garcés defected to Abd-ar-Rahman. The next year, Eneko's own son, Galindo Íñiguez and Mūsā's son Lubb ibn Mūsā went over to Córdoba, and Mūsā was forced to submit. Following a brief campaign the next year, 845, a general peace was achieved. In 850, Mūsā again rose in open rebellion, supported again by Pamplona, and envoys of Induo (thought to be Eneko) and Mitio, "Dukes of the Navarrese", were received at the French court. Eneko died in the Muslim year 237, which is late 851 or early 852, and was succeeded by García Íñiguez.

The name of the wife (or wives) of Eneko is not reported in contemporary records, although chronicles from centuries later assign her the name of Toda or Oneca. There is also scholarly debate regarding her derivation, some hypothesizing that she was daughter of Velasco, lord of Pamplona (killed 816), and others making her kinswoman of Aznar I Galíndez. He was father of the following known children:

Assona Íñiguez, who married her father's half-brother, Mūsā ibn Mūsā ibn Fortún ibn Qasi, lord of Tudela and Huesca

García Íñiguez, the future king

Galindo Íñiguez, fled to Córdoba where he was friend of Eulogio of Córdoba and became father of Mūsā ibn Galindo, Wali of Huesca in 860, assassinated in 870 in Córdoba

a daughter, wife of Count García el Malo (the Bad) of Aragón.

The dynasty founded by Eneko reigned for about 80 years, being supplanted by a rival dynasty in 905. However, due to intermarriages, subsequent kings of Navarre descend from Eneko.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%8D%C3%B1igo_Arista_of_Pamplona

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%8D%C3%B1igo_Arista_of_Pamplona

Íñigo Arista of Pamplona

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

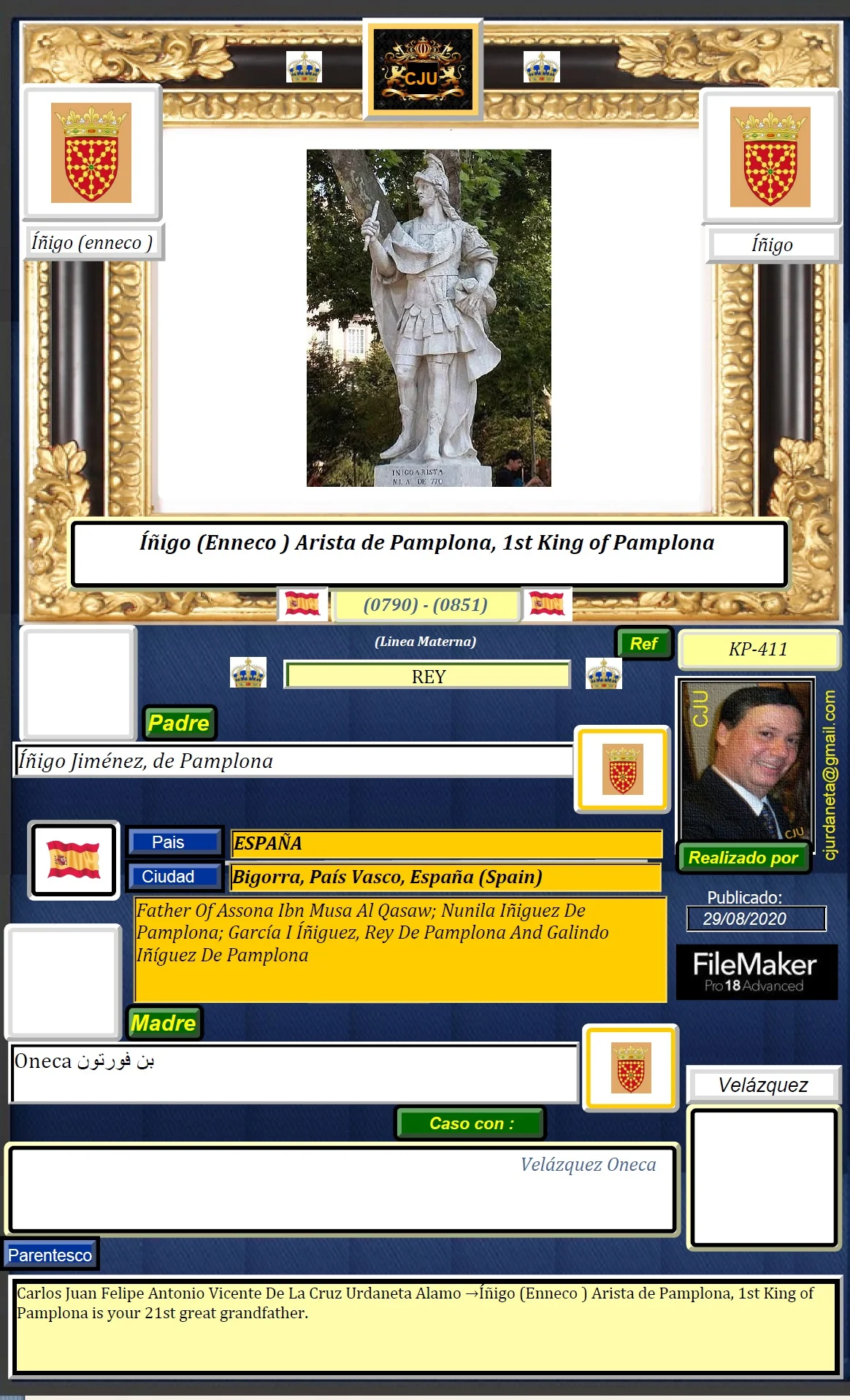

Statue in Madrid (José Oñate, 1750–53).

Íñigo Íñiguez Arista (Arabic: ونّقه بن ونّقه, Wannaqo ibn Wannaqo, Basque: Eneko Enekones Aritza/Haritza/Aiza; c. 790 – 851 or 852) was the first King of Pamplona (c. 824 – 851 or 852). He is said by a later chronicler to have been count of Bigorre, or at least to have come from there, but there is no near-contemporary evidence of this.[1]

Contents

[show]

* 1 Biography

* 2 References

o 2.1 Sources

o 2.2 Notes

[edit] Biography

His origin is obscure, but his patronymic indicates that he was the son of an Íñigo.[2] It has been speculated that he was kinsman of García Jiménez, who in the late 8th century succeeded his father Jimeno 'the Strong' in resisting Carolingian expansion into Vasconia. He is also speculated to have been related to the other Navarrese dynasty, the Jiménez.[3]

His mother also married Musa ibn Fortun ibn Qasi, by whom she was mother of Musa ibn Musa ibn Qasi, head of the Banu Qasi and Moslem ruler of Tudela, one of the chief lords of Valley of the Ebro.[4] Due to this relationship, Íñigo and his kin frequently acted in alliance with Musa ibn Musa and this relationship allowed Íñigo to extend his influence over large territories in the Pyrenean valleys.

The family came to power through struggles with Frankish and Muslim influence in Spain. In 799, pro-Frankish assassins murdered Mutarrif ibn Musa, governor of Pamplona, the brother of Musa ibn Musa ibn Qasi and perhaps of Íñigo himself. Ibn Hayyan reports that in 816, Abd al-Karim ibn Abd al-Wahid ibn Mugit launched a military campaign against the pro-Frankish "Enemy of God", Velasco the Gascon (Arabic: بلشك الجلشقي, Balašk al-Ŷalašqī), Sahib of Pamplona (Arabic: صاحب بنباونة), who had united Christian factions. They fought a three-day battle and the Christians were routed, with Velasco killed along with García López, maternal uncle of Alfonso II of Asturias, Sancho "the premier warrior/knight of Pamplona", and "Ṣaltān", similarly preeminent among the "pagans". This defeat of the pro-French force is said to have allowed the anti-French Íñigo to come to power. In 820, Íñigo is said to have intervened in the County of Aragon, ejecting a Frankish vassal, count Aznar I Galíndez, in favor of García el Malo (the Bad), who would become Íñigo's son-in-law. In 824, the Frankish counts Aeblus and Aznar Sánchez made an expedition against Pamplona, but were defeated in the third Battle of Roncesvalles. Traditionally, this battle led to the crowning of Íñigo as "King of Pamplona" but he continued to be called "Lord of Pamplona", as had his predecessor Velasco, by the Arabic chroniclers. Íñigo was a Christicolae princeps (Christian prince), according to Eulogio de Córdoba.[citation needed] However, his kingdom continually played Moslem and Christian against themselves and each other to maintain independence against outside powers.

In 840 his lands were attacked by Abd Allah ibn Kulayb, wali of Zaragoza, leading his half-brother, Musa ibn Musa into rebellion.[5] The next year, Íñigo fell victim to paralysis in battle against the Norse with Musa ibn Musa.[citation needed] His son García acted as regent, in concert with Fortún Íñiguez (Arabic: فرتون بن ونّقه, Fortūn ibn Wannaqo), "the premier knight of the realm", the king's brother and also half-brother of Musa. They joined Musa ibn Musa in an uprising against the Caliphate of Córdoba. Abd-ar-Rahman II, emir of Córdoba, launched reprisal campaigns in the succeeding years. In 843, Fortún Íñiguez was killed, and Musa unhorsed and forced to escape on foot, while Íñigo and his son Galindo escaped with wounds and several nobleman, most notably Velasco Garcés defected to Abd-ar-Rahman. The next year, Íñigo's own son, Galindo Íñiguez and Musa's son Lubb ibn Musa went over to Córdoba, and Musa was forced to submit. Following a brief campaign the next year, 845, a general peace was achieved.[6] In 850, Mūsā again rose in open rebellion, supported again by Pamplona,[7] and envoys of Induo (thought to be Íñigo) and Mitio,[8] "Dukes of the Navarrese", were received at the French court. Íñigo died in the Muslim year 237, which is late 851 or early 852, and was succeeded by García Íñiguez.[9]

The name of the wife (or wives) of Íñigo is not reported in contemporary records, although chronicles from centuries later assign her the name of Toda or Oneca.[10] There is also scholarly debate regarding her derivation, some hypothesizing that she was daughter of Velasco, lord of Pamplona (killed 816), and others making her kinswoman of Aznar I Galíndez[11]. He was father of the following known children:[12]

* Assona Íñiguez, who married her father's half-brother, Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortun ibn Qasi, lord of Tudela and Huesca

* García Íñiguez, the future king

* Galindo Íñiguez, fled to Córdoba where he was friend of Eulogio of Córdoba and became father of Musa ibn Galind, Amil of Huesca in 860, assassinated in 870 [13]

* a daughter, wife of Count García el Malo (the Bad) of Aragón.

The dynasty founded by Íñigo reigned for about 80 years, being supplanted by a rival dynasty in 905. However, due to intermarriages, subsequent kings of Navarre descend from Íñigo.

[edit] References

[edit] Sources

* Barrau-Dihigo, Lucien. Les origines du royaume de Navarre d'apres une théorie récente. Revue Hispanique. 7: 141-222 (1900).

* de la Granja, Fernando. "La Marca Superior en la obra de Al-'Udri". Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragon. 8:447-545 (1967).

* Lacarra de Miguel, José María. "Textos navarros del Códice de Roda". Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragon. 1:194-283 (1945).

* Lévi-Provençal, Évariste. "Du nouveau sur le Royaume de Pampelune au IXe Siècle". Bulletin Hispanique. 55:5-22 (1953).

* Lévi-Provençal, Évariste and Emilio García Gómez. "Textos inéditos del Muqtabis de Ibn Hayyan sobre los orígines del Reino de Pamplona". Al-Andalus. 19:295-315 (1954).

* Mello Vaz de São Payo, Luiz. "A Ascendência de D. Afonso Henriques". Raízes & Memórias 6:23-57 (1990).

* Pérez de Urbel, Justo. "Lo viejo y lo nuevo sobre el origin del Reino de Pamplona". Al-Andalus. 19:1-42 (1954).

* Sánchez Albernoz, Claudio. "La Epistola de S. Eulogio y el Muqtabis de Ibn Hayan". Princípe de Viana. 19:265-66 (1958).

* Sánchez Albernoz, Claudio. "Problemas de la historia Navarra del siglo IX". Princípe de Viana, 20:5-62 (1959).

* Settipani, Christian. La Noblesse du Midi Carolingien, Occasional Publiucations of the Unit for Prosopographical Research, Vol. 5. (2004).

* Stasser, Thierry. "Consanguinity et Alliances Dynastiques en Espagne au Haut Moyen Age: La Politique Matrimoniale de la Reinne Tota de Navarre". Hidalguia. No. 277: 811-39 (1999).

[edit] Notes

1. ^ Barrau-Dihigo

2. ^ Lacarra. A charter preserved at Leyre describes him as Enneco ... filius Simeonis (Íñigo Jiménez) and another Leyre document reports the obituary of Enneco Garceanes, que fuit vulgariter vocas Areista (Íñigo Garcés, called Arista), and later historians have followed one or the other of these, but both are thought to result from later corruption or forgery. 11th century chroniclers Ibn Hayyan and Al-Udri both call him ibn Wannaqo/Yannaqo (Íñiguez). Barrau-Dihigo.

3. ^ Lacarra

4. ^ Íñigo and Fortún Íñiguez are explicitly called brothers of Musa ibn Musa on their mother's side by chronclers Ibn Hayyan and Al-Udri. The order of the maternal marriages has been subject to speculation, with Lévi-Provençal and Pérez de Urbel having the widowed mother of Íñigo marrying Musà ibn Fortún, while Sánchez Albernoz ("Problemas") argued that the Christian marriage came after the Muslim.

5. ^ de la Granja, p. 468-9.

6. ^ Lévi-Provençal and García Gómez; Sánchez Albernoz ("Problemas")

7. ^ ibid

8. ^ Identified by Pérez de Urbel with Jimeno of Pamplona, but Sánchez Albernoz rejects this.

9. ^ Lévi-Provençal and García Gómez; Sánchez Albernoz ("Problemas"). It has been suggested that either Jimeno or his son García Jiménez served as regent following the death of Íñigo, but there is no evidence of this.

10. ^ Settipani

11. ^ Mello Vaz de São Payo;Stasser. These identifications are based on the names given in subsequent generations, but Sánchez Albernoz ("Problemas") wrote of the danger of assuming such name usage demonstrate specific familial linkages.

12. ^ Lacarra;Lévi-Provençal and García Gómez; Sánchez Albernoz, ("Problemas")

13. ^ Sánchez Albernoz ("S. Eulogio y el Muqtabis")

New title King of Pamplona

824–851/2 Succeeded by

García Íñiguez

This page was last modified on 13 July 2010 at 16:01.

Íñigo Íñiguez Arista (Arabic: ونقه بن ونقه, Wannaqo ibn Wannaqo, Basque: Eneko Enekones Aritza/Haritza/Aiza) (c. 790 – 851 or 852) was the first King of Pamplona (c. 824 – 851 or 852). He is said by a later chronicler to have been count of Bigorre, or at least to have come from there, but there is no near-contemporary evidence of this. His origin is obscure, but his patronymic indicates that he was the son of an Íñigo. It has been speculated that he was kinsman of García Jiménez, who in the late 8th century succeeded his father Jimeno 'the Strong' in resisting Carolingian expansion into Vasconia. He is also speculated to have been related to the other Navarrese dynasty, the Jiménez.

[source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%8D%C3%B1igo_Arista_of_Pamplona]

ñigo Íñiguez Arista (Arabic: ونّقه بن ونّقه, Wannaqo ibn Wannaqo, Basque: Eneko Enekones Aritza/Haritza/Aiza) (c. 790 – 851 or 852) was the first King of Pamplona (c. 824 – 851 or 852). He is said by a later chronicler to have been count of Bigorre, or at least to have come from there, but there is no near-contemporary evidence of this.[1] His origin is obscure, but his patronymic indicates that he was the son of an Íñigo.[2] It has been speculated that he was kinsman of García Jiménez, who in the late 8th century succeeded his father Jimeno 'the Strong' in resisting Carolingian expansion into Vasconia. He is also speculated to have been related to the other Navarrese dynasty, the Jiménez.[3]

His mother also married Musa ibn Fortun ibn Qasi, by whom she was mother of Musa ibn Musa ibn Qasi, head of the Banu Qasi and Moslem ruler of Tudela, one of the chief lords of Valley of the Ebro.[4] Due to this relationship, Íñigo and his kin frequently acted in alliance with Musa ibn Musa and this relationship allowed Íñigo to extend his influence over large territories in the Pyrenean valleys.

The family came to power through struggles with Frankish and Muslim influence in Spain.

The name of the wife (or wives) of Íñigo is not reported in contemporary records, although chronicles from centuries later assign her the name of Toda or Oneca.[10] There is also scholarly debate regarding her derivation, some hypothesizing that she was daughter of Velasco, lord of Pamplona (killed 816), and others making her kinswoman of Aznar I Galíndez[11]. He was father of the following known children:[12]

* Assona Íñiguez, who married her father's half-brother, Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortun ibn Qasi, lord of Tudela and Huesca

* García Íñiguez, the future king

* Galindo Íñiguez, fled to Córdoba where he was friend of Eulogio of Córdoba and became father of Musa ibn Galind, Amil of Huesca in 860, assassinated in 870 [13]

* a daughter, wife of Count García el Malo (the Bad) of Aragón.

The dynasty founded by Íñigo reigned for about 80 years, being supplanted by a rival dynasty in 905. However, due to intermarriages, subsequent kings of Navarre descend from Íñigo.

[edit] References

[edit] Sources

* Barrau-Dihigo, Lucien. Les origines du royaume de Navarre d'apres une théorie récente. Revue Hispanique. 7: 141-222 (1900).

* de la Granja, Fernando. "La Marca Superior en la obra de Al-'Udri". Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragon. 8:447-545 (1967).

* Lacarra de Miguel, José María. "Textos navarros del Códice de Roda". Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragon. 1:194-283 (1945).

* Lévi-Provençal, Évariste. "Du nouveau sur le Royaume de Pampelune au IXe Siècle". Bulletin Hispanique. 55:5-22 (1953).

* Lévi-Provençal, Évariste and Emilio García Gómez. "Textos inéditos del Muqtabis de Ibn Hayyan sobre los orígines del Reino de Pamplona". Al-Andalus. 19:295-315 (1954).

* Mello Vaz de São Payo, Luiz. "A Ascendência de D. Afonso Henriques". Raízes & Memórias 6:23-57 (1990).

* Pérez de Urbel, Justo. "Lo viejo y lo nuevo sobre el origin del Reino de Pamplona". Al-Andalus. 19:1-42 (1954).

* Sánchez Albernoz, Claudio. "La Epistola de S. Eulogio y el Muqtabis de Ibn Hayan". Princípe de Viana. 19:265-66 (1958).

* Sánchez Albernoz, Claudio. "Problemas de la historia Navarra del siglo IX". Princípe de Viana, 20:5-62 (1959).

* Settipani, Christian. La Noblesse du Midi Carolingien, Occasional Publiucations of the Unit for Prosopographical Research, Vol. 5. (2004).

* Stasser, Thierry. "Consanguinity et Alliances Dynastiques en Espagne au Haut Moyen Age: La Politique Matrimoniale de la Reinne Tota de Navarre". Hidalguia. No. 277: 811-39 (1999).

Íñigo Arista de Pamplona

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Íñigo Íñiguez, más conocido como Íñigo Arista o Eneko Aritza (c. 781 — 852), primer rey de Pamplona entre los años 810/820 y 852, Conde de Bigorra y de Sobrarbe. Se le considera patriarca de la dinastía Íñiga que sería la primera dinastía real de Pamplona.

Historia

Hijo de Íñigo Jiménez y Oneca. Muerto su padre, su madre se casó en segundas nupcias con el Banu Qasi Musá ibn Fortún de Tudela, uno de los señores del valle del Ebro, con cuyo apoyo llegó al trono. Este matrimonio dejó bajo la influencia de Íñigo Arista unos territorios considerables: desde Pamplona hasta los altos valles pirenaicos de Irati (Navarra) y Valle de Hecho (Aragón). Los Banu Qasi controlaban las fértiles riberas del Ebro, desde Tafalla hasta las cercanías de Zaragoza.

El advenimiento del primer rey de Navarra no se hizo sin dificultades. Entre los núcleos de población cristiana (minoritaria), algunos dan su apoyo al partido franco, sostenido primero por Carlomagno y más tarde por Luis el Piadoso. La rica familia cristiana de los Velasco está a la cabeza de ese partido.

En 799, unos procarolingios asesinan al gobernador de Pamplona Mutarrif ibn Muza, de la familia de los Banu Qasi. En 806, los francos controlan Navarra a través de un Velasco como gobernador. En 812, Luis el Piadoso manda una expedición contra Pamplona. El regreso no es muy glorioso, tomando como rehenes a niños y mujeres de la zona para protegerse durante el paso del puerto de Roncesvalles.

En 824 los condes francos Elbe y Aznar dirigen otra expedición contra Pamplona, pero son vencidos por Íñigo con el apoyo de sus yernos Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún y García el Malo de Jaca.

Entonces aparece Íñigo Arista como rey de Pamplona: "Christicolae princeps" (príncipe cristiano), según Eulogio de Córdoba.

El reino de Pamplona (más tarde de Navarra) nació, pues, de la alianza firme entre los musulmanes y los cristianos. Fruto de esta alianza fue la intervención en las luchas de los Banu Quasi con los Omeyas de Córdoba, lo que motivó las represalias de Abd al-Rahman II contra Pamplona.

En 841 es víctima de una enfermedad que lo deja paralítico. Su hijo García Íñiguez ejerce una fuerte regencia, llevando la dirección de las campañas militares. Pero la política de alianzas continúa. Así, su hija Assona se casa con Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún.

Descendencia [editar]Se casó con Oneca Velázquez, hija de Velasco, Señor de Pamplona, fallecido en 816.

Hijos:

Assona Íñiguez, casada con Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún, Walí de Tudela y Huesca.

García Íñiguez, sucesor en el trono.

Galindo Íñiguez de Pamplona, fallecido en 851 en Córdoba. Padre de:

Musa Ibn Galindo, Walí de Huesca 860, asesinado en 870 en Córdoba.

Nunila, casada con el Conde García “el Malo” de Aragón.

Conde de Bigorre y de Sobrarbe, I Rey de Pamplona 822

1. rey de Pamplona

Leo: Europäische Stammtafeln, J.A. Stargardt Verlag, Marburg, Schwennicke, Detlev (Ed.), Reference: II 53.

Leo: Some Ancient and Medieval Descents of Edward I of England, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2003., Stone, Don Charles, Compiler.

Iñigo Íñiguez, Enneco Enneconis (en latín) o Eneko Aritza (en euskera) (c. 7701 -851),2 primer rey de Pamplona entre los años 810/820 y 851, conde de Bigorra y de Sobrarbe. Se le considera patriarca de la dinastía Íñiga, que sería la primera dinastía real pamplonesa.

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Íñigo_Arista_de_Pamplona

Íñigo Arista (c. 781 - † 852), rey de Pamplona entre los años 810-820 y 852, conde de Bigorre y de Sobrarbe. Hijo de Íñigo Jiménez y Oneca. Muerto su padre, su madre se casó en segundas nupcias con el Banu Qasi Musá ibn Fortún de Tudela, uno de los señores del valle del Ebro, con cuyo apoyo llegó al trono. Este matrimonio dejó bajo la influencia de Íñigo Arista unos territorios considerables: desde Pamplona hasta los altos valles pirenáicos de Irati (Navarra), al valle de Hecho (Aragón). Los Banu Qasi controlan las fértiles riberas del Ebro, desde Tafalla hasta las cercanías de Zaragoza. Se le considera patriarca de la dinasía Íñiga que sería la primera dinastía real de Pamplona. El advenimiento del primer rey de Navarra no se hizo sin dificultades. Entre los núcleos de población cristiana (minoritaria), algunos dan su apoyo al partido franco, sostenido primero por Carlomagno, y más tarde por Luis el Piadoso. La rica familia cristiana de los Velasco está a la cabeza de ese partido. En 799, unos procarolingios asesinan al gobernador de Pamplona Mutarrif ibn Muza, de la familia de los Banu Qasi. En 806, los francos controlan Navarra a través de un Velasco como gobernador. En 812, Luis el Piadoso manda una expedición contra Pamplona. El regreso no es muy glorioso, tomando como rehenes a niños y mujeres de la zona para protegerse durante el paso de los puertos de Roncesvalles. En 824 los condes francos Elbe y Aznar dirigen otra expedición contra Pamplona, pero son vencidos por Íñigo con el apoyo de sus yernos, Musá ibn Fortún y García el Malo de Jaca. En entonces es cuando aparece Íñigo Arista como rey de Pamplona: "Christicolae princeps" (príncipe cristiano), según Eulogio de Córdoba. El reino de Pamplona (más tarde de Navarra), nació pues de la alianza firme entre los musulmanes y los cristianos. Fruto de esta alianza fue la intervención en las luchas de los Banu Quasi con los Omeyas de Córdoba, lo que motivó las represalias de Abd al-Rahman II contra Pamplona. En 841 es víctima de una enfermedad que lo deja paralítico. Su hijo García Íñiguez ejerce una fuerte regencia, llevando la dirección de las campañas militares. Pero la política de alianzas continúa. Así, su hija Assona se casa con con Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún. De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

royaume.europe... ;

Íñigo Íñiguez Arista (c. 790 – 851 or 852) was the first King of Pamplona (c. 824 – 851 or 852). He is said by a later chronicler to have been count of Bigorre, or at least to have come from there, but there is no near-contemporary evidence of this. His origin is obscure, but his patronymic indicates that he was the son of an Íñigo. It has been speculated that he was kinsman of García Jiménez, who in the late 8th century succeeded his father Jimeno in resisting Carolingian expansion into Vasconia. He is also speculated to have been related to the other Navarrese dynasty, the Jiménez.

His mother also married Mūsā ibn Fortún ibn Qasi, by whom she was mother of Mūsā ibn Mūsā ibn Qasi, head of the Banu Qasi and Moslem king of Tudela, one of the chief lords of Valley of the Ebro. Due to this relationship, Íñigo and his kin frequently acted in alliance with Mūsā ibn Mūsā and this relationship allowed Eneko to extend his influence over large territories in the Pyrenean valleys.

The family came to power through struggles with Frankish and Muslim influence in Spain. In 799, pro-Frankish assassins murdered Mutarrif ibn Mūsā, governor of Pamplona, the brother of Mūsā ibn Mūsā ibn Qasi and perhaps of Íñigo himself. In 820, Íñigo intervened in the County of Aragon, ejecting a Frankish vassal, count Aznar I Galíndez, in favor of García el Malo (the Bad, who would become Íñigo's son-in-law. In 824, the Frankish counts Aeblus and Aznar Sánchez made an expedition against Pamplona, but were defeated in the third Battle of Roncesvalles. The Basque victors are not named, but it was in the context of this defeat that Íñigo is said to have been pronounced "King of Pamplona" in that city by the people. Íñigo was a Christicolae princeps (Christian prince), according to Eulogio de Córdoba. However, his kingdom continually played Moslem and Christian against themselves and each other to maintain independence against outside powers.

In 840 his lands were attacked by Abd Allah ibn Kulayb, wali of Zaragoza, leading his half-brother, Mūsā ibn Mūsā into rebellion. The next year, Eneko fell victim to paralysis in battle against the Norse with Mūsā ibn Mūsā. His son García acted as regent, in concert with Fortún Íñiguez, "the premier knight of the realm", the king's brother and also half-brother of Mūsā. They joined Mūsā ibn Mūsā in an uprising against the Caliphate of Córdoba. Abd-ar-Rahman II, emir of Córdoba, launched reprisal campaigns in the succeeding years. In 843, Fortún Íñiguez was killed, and Mūsā unhorsed and forced to escape on foot, while Eneko and his son Galindo escaped with wounds and several nobleman, most notably Velasco Garcés defected to Abd-ar-Rahman. The next year, Eneko's own son, Galindo Íñiguez and Mūsā's son Lubb ibn Mūsā went over to Córdoba, and Mūsā was forced to submit. Following a brief campaign the next year, 845, a general peace was achieved. In 850, Mūsā again rose in open rebellion, supported again by Pamplona, and envoys of Induo (thought to be Eneko) and Mitio, "Dukes of the Navarrese", were received at the French court. Eneko died in the Muslim year 237, which is late 851 or early 852, and was succeeded by García Íñiguez.

The name of the wife (or wives) of Eneko is not reported in contemporary records, although chronicles from centuries later assign her the name of Toda or Oneca. There is also scholarly debate regarding her derivation, some hypothesizing that she was daughter of Velasco, lord of Pamplona (killed 816), and others making her kinswoman of Aznar I Galíndez. He was father of the following known children:

Assona Íñiguez, who married her father's half-brother, Mūsā ibn Mūsā ibn Fortún ibn Qasi, lord of Tudela and Huesca

García Íñiguez, the future king

Galindo Íñiguez, fled to Córdoba where he was friend of Eulogio of Córdoba and became father of Mūsā ibn Galindo, Wali of Huesca in 860, assassinated in 870 in Córdoba

a daughter, wife of Count García el Malo (the Bad) of Aragón.

The dynasty founded by Eneko reigned for about 80 years, being supplanted by a rival dynasty in 905. However, due to intermarriages, subsequent kings of Navarre descend from Eneko.

Inigo Enneconis (in Latin) or Eneko Aritza (in euskera) (c.770 [1] - 851), [2] first king of Pamplona between the years 810/820 and 851, count of Bigorra and king of Sobrarbe .[3] [4] He is considered patriarch of the Íñiga dynasty, which would be the first real Pamplona dynasty.

Son of Íñigo Fortun and Oneca. The Íñiga or Eneconis, founder of the Real House of Pamplona-Navarra, comes from a line different from the dynasty Jimena, being both of root of extractions very different, although very related with each other . One is known visigoda, coming from an Eneco, Conde de Calahorra, closely linked to that of Fortún, Count of Borja, and the other Aquitaine-cantabrica, direct descendant of the great Duke Eudon of Aquitaine (through the line Lope-Alarico- Seimino or Jimeno) as it establishes important works realized in this respect. The confusion is due to the late appearance of Íñigo Jiménez, brother of the co-regent García Jiménez and children both of Seimino, contemporaries of the king García I Íiguez And confused in names and in chronology.

When his father died, his mother remarried with the Banu Qasi Musa ibn Fortun of Tudela, one of the lords of the Ebro valley, whose support came to the throne, and who were the parents of Musa ibn Musa. This marriage left under the influence of Íñigo Arista considerable territories: from Pamplona to the high Pyrenean valleys of Irati (Navarra) and Valle de Hecho (Aragon). The Banu Qasi controlled the fertile banks of the Ebro, from Tafalla to the outskirts of Zaragoza.

The advent of the first king of Pamplona was not without difficulty. Among the nuclei of Christian (minority) population, some give their support to the Frankish party, held first by Charlemagne and later by Louis the Pious. The rich Christian family of the Velasco is at the head of that party.

In 799, procarolingios assassinate to the governor of Pamplona, relative of Íñigo Arista, Mutarrif ibn Muza, great-granddaughter of the count Casio. In 806, the Franks control Navarra through a Velasco like governor. In 812, Luis the Pious sends an expedition against Pamplona. The return is not very glorious, taking hostage children and women of the area to protect themselves during the passage of the port of Roncesvalles.

In 824 the Frankish counts Elbe and Aznar lead another expedition against Pamplona, but they are defeated by Íñigo with the support of his sons-in-law Musa ibn Musa and García el Malo de Jaca. Íñigo Arista is named by three hundred knights king, in Peña de Oroel, Jaca.

Then Íñigo Arista appears like princeps: "Christicolae princeps" (Christian prince), according to Eulogio of Cordova.

Fruit of this alliance was the intervention in the fights of Banu Quasi with the Umayyads of Cordova, which motivated the reprisals of Abderramán II against Pamplona.

In 841 he is the victim of a disease that leaves him paralyzed. His son García Íñiguez exerts a strong regency, leading the direction of the military campaigns. But the alliance policy continues. Thus, his daughter Assona marries his uncle Musa ibn Musa. According to Lévi-Provençal, it could be polygamous, like its relatives the Banu Qasi. [1] He was the father of:

Assona Íñiguez, married in 820 with Musa ibn Musa, I valued Tudela and Huesca, his half-uncle to be the uterine brother of his father Íñigo Arista. [1] Garcia Iniguez, successor to the throne, who served as regent when his father was paralyzed. [7] [1] Galindo Íñiguez de Pamplona, [7] murdered in 843, [1] was the father of Musa ibn Galindo, a valiant of Huesca in 860 and murdered in 870 in Cordoba. A daughter of unknown name married to the count Garcia "the Malo" of Aragon. [

<Hr>

II - ARGENTINE ISLAND "the Vascon." (Eneko Aritza)

Born ~ 781, died in 852. Conde de Bigorre and Sobrarbe, I King of Pamplona 822. He married:

ONECA VELÁZQUEZ, daughter of Velasco, Lord of Pamplona; Died in 816. Parents of:

1.- Assona Íñiguez, married Musa ibn Musa ibn Fortún, Walí de Tudela and Huesca. C / s.

2.- García I Íiguez, follow the line.

3.- Galindo Íñiguez de Pamplona, who died in 851 in Cordoba. Father of:

A.- Musa Ibn Galindo, Walí de Huesca 860, murdered in 870 in Cordoba.

4.- Nunila, married with Count Garcia "the Bad" of Aragon.

Íñigo Arista o Íñigo Íñiguez a (m. 851) fue el fundador de la dinastía Arista-Íñiga, y conde de Bigorra. Aunque tradicionalmente ha sido considerado el primer rey de Pamplona, hoy muchos historiadores prefieren hablar de «reino en estado latente» para el Estado que Arista y sus descendientes García Íñiguez y Fortún Garcés acaudillaron entre 824 y 905. 1 Así pues, según esta interpretación estos tres miembros de la dinastía Íñiga fueron más bien caudillos, y no reyes. En cualquier caso, Arista obtuvo el liderazgo con el apoyo de sus parientes, los Banu Qasi, e hizo frente a una expedición franca a la que derrotó en la segunda batalla de Roncesvalles.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%8D%C3%B1igo_Arista

=======================

Íñigo Arista (Basque: Eneko, Arabic: ونّقه, Wannaqo, c. 790 – 851 or 852) was a Basque leader, considered the first King of Pamplona. He is thought to have risen to prominence after the defeat of local Frankish partisans in 816, and his rule is usually dated from shortly after the defeat of a Carolingian army in 824.

He is first attested by chroniclers as a rebel against the Emirate of Córdoba from 840 until his death a decade later. Remembered as the nation's founder, he would be referred to as early as the 10th century by the nickname "Arista", coming either from Basque Aritza (Haritza/Aiza, literally 'the oak', meaning 'the resilient') or Latin Aresta ('the considerable').

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%8D%C3%B1igo_Arista_of_Pamplona

https://www.nubeluz.es/cristianos/navarra/arista.html

read more

View All

Immediate Family

Text View

Showing 12 of 16 people

Oneca Velázquez

wife

Assona ibn Musa al Qasaw

daughter

Nunila Iñiguez de Pamplona

daughter

García I Íñiguez, rey de Pamp...

son

Galindo Iñíguez de Pamplona

son

Íñigo Jiménez, de Pamplona

father

Oneca بن فورتون

mother

Fortún Iñiguez de Pamplona

brother

Musa Ibn Fortún ibn Qasi, valì...

stepfather

Musa Ibn Musa o Muza Ibn Muza o ...

half brother

Mutarrif ibn Musa, valí de Huesca

half brother

Jonás (Yunus) ibn Musa

half brother