30 ° Bisabuelo de: Carlos Juan Felipe Antonio Vicente De La Cruz Urdaneta Alamo

____________________________________________________________________________

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

(Linea Paterna)

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

'Nathan HaBabli' ben Abu Ishaq Avraham Nasi, 2nd. Exilarca Mar Uqba HaRofeh, Qadi al-Qayraw ben Abu Ishaq Avraham, Exilarch 'Mar Uqba HaRofeh', Qadi al-Qayrawānī is your 30th great grandfather.You→ Carlos Juan Felipe Antonio Vicente De La Cruz Urdaneta Alamo→ Enrique Jorge Urdaneta Lecuna

your father → Carlos Urdaneta Carrillo

his father → Enrique Urdaneta Maya, Dr.

his father → Josefa Alcira Maya de la Torre y Rodríguez

his mother → Vicenta Rodríguez Uzcátegui

her mother → María Celsa Uzcátegui Rincón

her mother → Sancho Antonio de Uzcátegui Briceño

her father → Jacobo de Uzcátegui Bohorques

his father → Luisa Jimeno de Bohorques Dávila

his mother → Juan Jimeno de Bohórquez

her father → Luisa Velásquez de Velasco

his mother → Juan Velásquez de Velasco y Montalvo, Gobernador de La Grita

her father → Ortún Velázquez de Velasco

his father → María Enríquez de Acuña

his mother → Inés Enríquez y Quiñones

her mother → Fadrique Enríquez de Mendoza, 2º Almirante Mayor de Castilla, Conde de Melgar y Rueda

her father → Alonso Enríquez de Castilla, 1er. Almirante Mayor de Castilla, Señor de Medina de Rio Seco

his father → Yonati bat Gedaliah, Paloma

his mother → Gedalia Shlomo ibn ben Shlomo ibn Yaḥyā haZaken

her father → Shlomo ben Yahya ibn Yahya

his father → Yosef ibn Yahya HaZaken

his father → Don Yehuda ibn Yahya ibn Ya'ish

his father → Don Yahya "el Negro"

his father → Yehudah "Ya'ish" ben Yahuda ibn ben Yahudah ibn Yaḥyā, senhor de Aldeia dos Negros

his father → Hayy "Hiyya" ibn Ya'ish ibn Ya'ish ben ben David al-Daudi, HaNasi

his father → David "Ya'ish" ibn Hiyya

his father → Yehudah Hayy "Yahya" ben Hiyya, Nasi, Ra'is b'Rabbanan al-Tulaytula

his father → Ṣāʿid al-Andalusī "Hiyya al-Daudi", Qaḍī of Cordoba & Toledo

his father → Abu Suleiman David ibn Yaʿīs̲h̲ ben Yehuda Ibn Ya Ish ben Zakai II ben Zakai II, Nasi, Qāḍī, haDayyan of Toledo

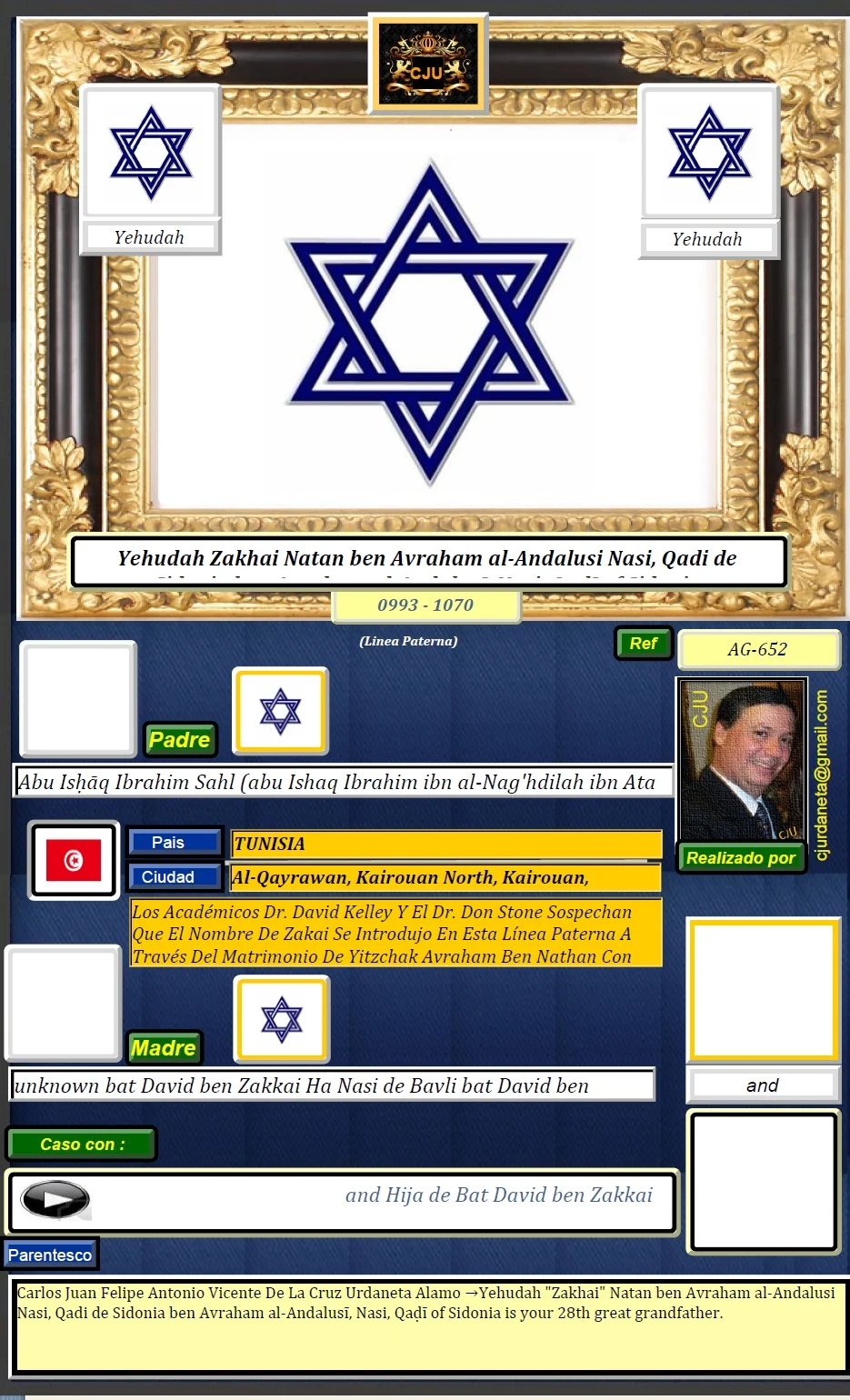

his father → Yehudah "Zakhai" Natan ben Avraham al-Andalusi Nasi, Qadi de Sidonia ben Avraham al-Andalusī, Nasi, Qaḍī of Sidonia

his father → Abu Isḥāq Ibrahim Sahl (abu Ishaq Ibrahim ibn al-Nag'hdilah ibn Ata al-Yahudi, haRoffeh) Exilarch, Rosh Golah of Judah ibn al-Nag'hdīlah ibn Ata al-yahūdī, haRoffe al-Galut 'Mar Sahl'

his father → 'Nathan HaBabli' ben Abu Ishaq Avraham Nasi, 2nd. Exilarca Mar Uqba HaRofeh, Qadi al-Qayraw ben Abu Ishaq Avraham, Exilarch 'Mar Uqba HaRofeh', Qadi al-Qayrawānī

his fatherShow short path | Share this path

You might be connected in other ways.

Show Me

'Nathan HaBabli' ben Abu Ishaq Avraham Nasi, 2nd. Exilarca Mar Uqba HaRofeh, Qadi al-Qayraw ben Abu Ishaq Avraham, Exilarch 'Mar Uqba HaRofeh', Qadi al-Qayrawānī MP

Gender: Male

Birth: circa 940

Baghdad, Baghdād, Iraq

Death: circa 1049 (101-117)

Ramla, Israel

Immediate Family:

Son of David Avraham ben Hazub, Exilarch 'Rab David II', haSofer b'Pumbeditha and unknown

Husband of ??? bat Mevorakh ben Eli

Father of Abu Isḥāq Ibrahim Sahl (abu Ishaq Ibrahim ibn al-Nag'hdilah ibn Ata al-Yahudi, haRoffeh) Exilarch, Rosh Golah of Judah ibn al-Nag'hdīlah ibn Ata al-yahūdī, haRoffe al-Galut 'Mar Sahl'; Abu ’l-Hasan ʿAlī ben al-Sh̲aybānī al-Kātib al-Mag̲h̲ribī al-Qayrawānī Ibn Abi ’l-Rid̲j̲āl and ʿAbd Allāh ben Muḥammad al-Manṣūriyya

Brother of Yehuda "Zakai" ben David, 29th Exilarch 'Judah II'

Added by: Alex Ronald Keith Paz on June 14, 2008

Managed by: Alex Ronald Keith Paz and 9 others

Curated by: Jaim David Harlow, J2b2a1a1a1b3c

0 Matches

Research this Person

Contact Profile Managers

View Tree

Edit Profile

Overview

Media

Timeline

Discussions

Sources

Revisions

DNA

About

English (default) history

Nathan Ha-Bavli has been an enigmatic figure - but I think I have narrowed down to EXACTLY who is Nathan Ha-Bavli. Here is a short description of previous attempts to identify Nathan Ha-Bavli:

Since Nathan b. Jehiel of Rome, the author of the "'Aruk," is quoted in Zacuto's "Yuḥasin" (ed. Filipowski, p. 174, London, 1856) as "Nathan ha-Babli of Narbonne," Grätz ("Gesch." 3d ed., v. 288, 469-471) mistook the latter for Nathan ben Isaac ha-Kohen ha-Babli and ascribed to him an "'Aruk" similar to that written by Nathan b. Jehiel.

Grätz even went so faras to identify Nathan ben Isaac with the fourth of the four prisoners captured by Ibn Rumaḥis (see Ḥushiel ben Elhanan), assuming that he settled afterward at Narbonne. In fact, Grätz was very close, as Nathan was the Exilarch who sat in the seat of Gaon of Corboba until 'Rab Moshe ben Hanoch' arrived...it was Nathan (in his role as 'Mar Uqba haRofe') who turned over the Academy to a premier Rosh Golah who was expert in the Babylonian traditions of jurisprudence, exegesis, Talmudic study and Halacha. My research leads me to believe that Nathan was a schemer who helped orchestrate the "4 hostages" scenario in order to salvage the best sages of Babylon as those Academies waned - while he himself was one of those auctioned.

Nathan ha-Bavlī - the 4th Prisoner of ibn Rumaḥis

Nathan ben Isaac ha-Kohen ha-Bavli is the otherwise unknown author of a brief but very important historical text concerning the Babylonian academies and the exilarchate. The work, entitled Akhbār Baghdād (A Chronicle of Baghdad), was apparently written in Judeo-Arabic in North Africa in the mid-tenth century, but the sobriquet ha-Bavli indicates that Nathan came from Babylonia (Iraq). His account has been preserved in an undated Hebrew translation published by A. Neubauer. Fragments of the Judeo-Arabic original found in the Cairo Geniza were subsequently published by I. Friedlander and M. Ben-Sasson.

Akhbār Baghdād is organized in two sections. The first gives a detailed history of two major controversies involving factions of the Iraqi leadership: a fiscal dispute between the gaon of Pumbedita and the exilarch ‘Uqba [himself], which resulted in the latter’s exile from Baghdad (an event unknown from other sources but tentatively dated to the early tenth century), and the well-known rift between Sa‘adya Gaon and ‘Uqba’s apparent successor, the exilarch David ben Zakkay. The second section is a generic account of the functions and prerogatives of the exilarchate and the academies, including an elaborate description of the exilarch’s investiture (which stresses the royal trappings of the office), and a rare description of the daily routine of the gaonic academies during the kalla months (when all the students were in attendance).

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Nathan Ha-Bavli ha sido una figura enigmática, pero creo que me he reducido a EXACTAMENTE quién es Nathan Ha-Bavli. Aquí hay una breve descripción de los intentos anteriores para identificar a Nathan Ha-Bavli:

Desde Nathan b. Jehiel de Roma, el autor de "'Aruk", es citado en "Yuḥasin" de Zacuto (ed. Filipowski, p. 174, Londres, 1856) como "Nathan ha-Babli de Narbonne", Grätz ("Gesch". 3d ed., v. 288, 469-471) confundió este último con Nathan ben Isaac ha-Kohen ha-Babli y le atribuyó un "'Aruk" similar al escrito por Nathan b. Jehiel

Grätz llegó incluso a identificar a Nathan ben Isaac con el cuarto de los cuatro prisioneros capturados por Ibn Rumaḥis (ver Ḥushiel ben Elhanan), suponiendo que se estableció después en Narbonne. De hecho, Grätz estaba muy cerca, ya que Nathan era el Exilarch que se sentó en el asiento de Gaon de Corboba hasta que llegó 'Rab Moshe ben Hanoch' ... fue Nathan (en su papel de 'Mar Uqba haRofe') quien se entregó la Academia a un primer ministro Rosh Golah, experto en las tradiciones de jurisprudencia, exégesis, estudio talmúdico y halajá de Babilonia. Mi investigación me lleva a creer que Nathan fue un intrigante que ayudó a orquestar el escenario de los "4 rehenes" con el fin de salvar a los mejores sabios de Babilonia a medida que esas Academias disminuían, mientras que él mismo era uno de los subastados.

Nathan ha-Bavlī - el 4to prisionero de ibn Rumaḥis

Nathan ben Isaac ha-Kohen ha-Bavli es el autor desconocido de un texto histórico breve pero muy importante sobre las academias babilónicas y el exilarcado. La obra, titulada Akhbār Baghdād (Una crónica de Bagdad), aparentemente fue escrita en judeoárabe en el norte de África a mediados del siglo X, pero el apodo ha-Bavli indica que Nathan vino de Babilonia (Iraq). Su relato se ha conservado en una traducción hebrea sin fecha publicada por A. Neubauer. Posteriormente, I. Friedlander y M. Ben-Sasson publicaron fragmentos del original judeoárabe encontrado en El Cairo Geniza.

Akhbār Baghdād está organizado en dos secciones. El primero da una historia detallada de dos controversias importantes que involucran a facciones de la dirección iraquí: una disputa fiscal entre el gaon de Pumbedita y el exilarch 'Uqba [mismo], que resultó en el exilio de Bagdad (un evento desconocido de otras fuentes pero datada tentativamente a principios del siglo X), y la conocida grieta entre Sa'adya Gaon y el aparente sucesor de 'Uqba, el exilarch David ben Zakkay. La segunda sección es un recuento genérico de las funciones y prerrogativas del exilarcado y las academias, que incluye una descripción elaborada de la investidura del exilarco (que enfatiza los adornos reales de la oficina), y una descripción rara de la rutina diaria de las academias gaónicas. durante los meses de kalla (cuando todos los estudiantes asistieron).

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

The opening lines of Akhbār Baghdād state that it recounts “that which [Nathan] partly saw and partly heard,” and at least portions of his account do appear to reflect firsthand experience. Since he has a tendency to generalize on the basis of isolated occurrences, however, his depiction of the Iraqi leadership, while invaluable, must be treated with caution. The suggestion that the known text of Akhbār Baghdād may have been excerpted from a lost longer composition was rejected by Ben-Sasson, who concludes from manuscript and literary evidence that the extant Hebrew version is a freely rendered but essentially faithful translation of the original work in its entirety.

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Las primeras líneas de Akhbār Baghdād afirman que cuenta "lo que [Nathan] vio y escuchó en parte", y al menos partes de su relato parecen reflejar experiencia de primera mano. Sin embargo, dado que tiene una tendencia a generalizar sobre la base de sucesos aislados, su descripción del liderazgo iraquí, aunque invaluable, debe tratarse con precaución. La sugerencia de que el texto conocido de Akhbār Baghdād puede haber sido extraído de una composición más larga perdida fue rechazada por Ben-Sasson, quien concluye a partir de manuscritos y evidencia literaria que la versión hebrea existente es una traducción libremente traducida pero esencialmente fiel de la obra original en en su totalidad

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Eve Krakowski

Bibliography

Ben-Sasson, Menahem. “The Structure, Goals, and Content of the Story of Nathan ha-Babli,” in Culture and Society in Medieval Jewry: Studies Dedicated to the Memory of Haim Hillel Ben-Sasson, ed. M. Ben-Sasson, R. Bonfil, and J. Hacker (Jerusalem: Merkaz Shazar, 1989), pp. 137–196 [Hebrew].

Brody, Robert. The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), pp. 26–30.

Friedlander, I. “The Arabic Original of the Report of R. Nathan Hababli,” Jewish Quarterly Review, o.s. 17 (1905): 747–761.

Gil, Moshe. Jews in Islamic Countries in the Middle Ages (Leiden: Brill, 2004), pp. 209–217 et passim.

Neubauer, Adolf. Mediaeval Jewish Chronicles and Chronological Notes (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1887–95), vol. 2, pp. 78–88.

Citation Eve Krakowski. " Nathan ha-Bavlī." Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Executive Editor Norman A. Stillman. Brill Online , 2013. Reference. Jim Harlow. 16 January 2013

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Details about Nathan Ha-Bavli -----------------------------------------

Physician to Fatimid Caliph in Kairouan; Nathan left Palestine for North Africa in Service of the Fatimids who deposed his father, David and controlled North Africa. In 972 the Fatimids moved their base to Egypt. Around 1011 Nathan traveled from Cordoba to Kairouan to settle the estate of his father, who had died there. While in Africa he studied in Kairouan with Chushiel ben Elchanan; Nathan left Kairouan, revered as a mathematics genius, and went to Fostat where he became more closely aligned with the Karaites.

Nathan's alignment with the Karaites stems from him being exiled to the Maghrib after losing an argument of the distribution of monies to Sura and Pumbeditha academies. Due to his friendly relations with Karaites, he was stripped of his ability to confer titles and rights to members of the community – in fact his name is removed from the list of Exilarchs for having instigated the support of heretics (Karaites) and events which led to the bloodshed in Tyre. His name was stripped and his name is no longer mentioned among the list of Nagidim of Egypt; however, he was the very “first Nagid of Egypt as Physician to the Fatimid Caliph”.

After the death of his maternal uncle, Rav ben Yohai, av bet din of the academy of Erez Israel, Nathan claimed the position - although according to accepted custom it belonged to Tobiah, who ranked third in the academy - at the same time attempting to oust Rabbi Solomon ben Yehuda as Gaon of the academy. In the struggle, Nathan was sponsored by Diaspora scholars, while Solomon ben Yehuda was supported by the local community and also favored by the Fatimid governor of Ramleh.

Nathan lived in Ramleh, attempting to assume the functions of gaon there, while Solomon still held his position in Jerusalem and issued a ban against Nathan. In 1042 both parties agreed that Nathan should succeed Solomon as gaon of the academy after the latter's death. However, when this occurred (before 1051) the office of gaon passed to Daniel ben Azariah. Nothing is known of Nathan's teachings. In one of his letters of 1042 he mentions his son Abraham, whose son Nathan was later av bet din of the academy.

He was Gaon of Yeshivat Eretz Ha-Tsvi where we remained Av Beit Din until his death around 1048 CE. Insofar as scholarship is concerned, Nathan is credited with an Arabic commnetary on the Mishneh of Yehudah HaNasi the text of which is preserved in Yemenite version of the Mishneh [having been copied by Yahya and Yosef ben David Qafih (Qapach). This writer suspects that Nathan's name is omitted from the list, and his son's names are portrayed in Arabic so as to distance the sons from the misdeeds of Nathan. Nathan has at least one son,

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Médico del califa fatimí en Kairuán; Nathan dejó Palestina para ir al norte de África al servicio de los fatimíes que depusieron a su padre, David, y controlaron el norte de África. En 972 los fatimíes trasladaron su base a Egipto. Alrededor de 1011, Natán viajó desde Córdoba a Kairuán para establecer la propiedad de su padre, que había muerto allí. Mientras estuvo en África estudió en Kairouan con Chushiel ben Elchanan; Nathan dejó Kairouan, venerado como un genio de las matemáticas, y fue a Fostat donde se alineó más estrechamente con los caraítas.

La alineación de Nathan con los caraítas se debe a que fue exiliado al Magreb después de perder una discusión sobre la distribución de dinero a las academias Sura y Pumbeditha. Debido a sus relaciones amistosas con Karaites, fue despojado de su capacidad para conferir títulos y derechos a los miembros de la comunidad; de hecho, su nombre se elimina de la lista de Exilarchs por haber instigado el apoyo de los herejes (Karaites) y los eventos que llevaron al derramamiento de sangre en Tiro. Su nombre fue despojado y su nombre ya no se menciona entre la lista de Nagidim de Egipto; sin embargo, fue el "primer Nagid de Egipto como médico del califa fatimí".

Después de la muerte de su tío materno, Rav ben Yohai, quien apostó en la academia de Erez Israel, Nathan reclamó el puesto, aunque según la costumbre aceptada, pertenecía a Tobiah, que ocupaba el tercer lugar en la academia, al mismo tiempo que intentaba Expulsar al rabino Solomon ben Yehuda como Gaon de la academia. En la lucha, Nathan fue patrocinado por eruditos de la diáspora, mientras que Solomon ben Yehuda fue apoyado por la comunidad local y también favorecido por el gobernador fatimí de Ramleh.

Nathan vivía en Ramleh, intentando asumir las funciones de gaon allí, mientras Salomón aún mantenía su posición en Jerusalén y prohibió a Nathan. En 1042, ambas partes acordaron que Nathan debería suceder a Salomón como gaon de la academia después de la muerte de este último. Sin embargo, cuando esto ocurrió (antes de 1051) el oficio de gaon pasó a Daniel ben Azariah. No se sabe nada de las enseñanzas de Nathan. En una de sus cartas de 1042 menciona a su hijo Abraham, cuyo hijo Nathan fue más tarde defensor de la academia.

Fue Gaon de Yeshivat Eretz Ha-Tsvi donde permanecimos en Av Beit Din hasta su muerte alrededor de 1048 CE. En lo que respecta a la erudición, a Nathan se le atribuye un comité árabe en la Mishneh de Yehudah HaNasi, cuyo texto se conserva en la versión yemenita de la Mishneh [que fue copiada por Yahya y Yosef ben David Qafih (Qapach). Este escritor sospecha que el nombre de Nathan se omite de la lista, y los nombres de su hijo están representados en árabe para distanciar a los hijos de las fechorías de Nathan. Nathan tiene al menos un hijo,

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Nathan ben Abraham was a/k/a Abū Sahl Nathan ben Abraham ben Saul, a member of a gaonic family on his mother’s side, was born in Palestine in the last quarter of the tenth century. He went to Qayrawan around 1011 in connection with an inheritance left by his father, but remained there to study under Ḥushiel ben Ḥananel. In Qayrawan, and later in Fustat, he engaged in commerce and made many important friends. His wife was the daughter of Mevorakh ben Eli, one of Fustat’s wealthier citizens. Around age forty, he returned to Palestine, where he was warmly received by the gaon, Solomon ben Judah. Nathan demanded to be appointed av bet din (president of the court), the number-two position in the yeshiva, a post held by his recently deceased uncle. The rightful heir to the post was Tuvia, the “third” in the yeshiva, but he relinquished his claim in Nathan’s favor in order to preserve harmony, despite the gaon’s displeasure with this breach of tradition.

This incident marked the eruption of a rivalry involving the descendants of the three families that had valid claims to the Palestinian gaonate, with Joseph and Elijah ha-Kohen, the sons of Solomon ha-Kohen—Solomon ben Judah’s predecessor in the gaonate—also joining the fray. There was already some bitterness toward Solomon ben Judah, and questions had been raised about his integrity, especially with respect to appointments he had made. As a result, Nathan ben Abraham’s supporters declared him gaon in place of Solomon ben Judah.

Serious dissension broke out in Tishre 1038 during the Hoshana Rabba ceremony on the Mount of Olives and at the assembly in the great synagogue of Ramle, where each faction sat on a different side and declared its leader gaon. By the summer of 1039, the Jewish communities along the Mediterranean littoral were in a state of turmoil. Jerusalem, Ramle, Fustat, Qayrawan, and undoubtedly many other communities were torn into factions. In Fustat, verbal disputes led to physical assaults, and the Fatimid police closed the Jerusalemite synagogue for two years. The two sides vied for the support of the Fatimid government, and finally, after the conflict had dragged on for more than four years, government intervention brought it to an end.

On Hoshana Rabba 1042, the two sides arrived at an agreement stipulating that Solomon ben Judah would continue as gaon and Nathan ben Abraham would be the av bet din, but under the strict supervision of the sons of the late gaon Solomon ha-Kohen, the “fourth” and “fifth” in the yeshiva. Tuvia ben Daniel continued as “third.” The agreement was signed by all the members of the yeshiva, as well as the Karaite nesi’im, who had sided with Nathan ben Abraham. Although Nathan became av bet din, he died three years later and never became gaon, whereas Solomon ben Judah continued to occupy the post for many years to come.

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Nathan ben Abraham era un / k / a Abū Sahl Nathan ben Abraham ben Saul, miembro de una familia gaónica del lado de su madre, nació en Palestina en el último cuarto del siglo X. Fue a Qayrawan alrededor de 1011 en relación con una herencia dejada por su padre, pero permaneció allí para estudiar con Ḥushiel ben Ḥananel. En Qayrawan, y más tarde en Fustat, se dedicó al comercio e hizo muchos amigos importantes. Su esposa era hija de Mevorakh ben Eli, uno de los ciudadanos más ricos de Fustat. Alrededor de los cuarenta años, regresó a Palestina, donde fue recibido calurosamente por el gaon, Solomon ben Judah. Nathan exigió ser nombrado av bet din (presidente de la corte), el puesto número dos en la yeshiva, un puesto ocupado por su tío recientemente fallecido. El heredero legítimo del cargo fue Tuvia, el "tercero" en la yeshiva, pero renunció a su reclamo a favor de Nathan para preservar la armonía, a pesar del descontento del gaon con esta violación de la tradición.

Este incidente marcó la erupción de una rivalidad que involucraba a los descendientes de las tres familias que tenían reclamos válidos para el gaonato palestino, con Joseph y Elijah ha-Kohen, los hijos de Salomón ha-Kohen, el predecesor de Solomon ben Judah en el gaonato, también se unieron la refriega. Ya había cierta amargura hacia Solomon ben Judah, y se habían planteado preguntas sobre su integridad, especialmente con respecto a las citas que había hecho. Como resultado, los partidarios de Nathan ben Abraham lo declararon gaon en lugar de Solomon ben Judah.

Se produjo una gran disensión en Tishre 1038 durante la ceremonia de Hoshana Rabba en el Monte de los Olivos y en la asamblea en la gran sinagoga de Ramle, donde cada facción se sentó en un lado diferente y declaró que su líder era gaon. Para el verano de 1039, las comunidades judías a lo largo del litoral mediterráneo estaban en un estado de agitación. Jerusalén, Ramle, Fustat, Qayrawan y, sin duda, muchas otras comunidades fueron divididas en facciones. En Fustat, las disputas verbales condujeron a agresiones físicas, y la policía fatimí cerró la sinagoga de Jerusalén por dos años. Las dos partes compitieron por el apoyo del gobierno fatimí y, finalmente, después de que el conflicto se prolongó durante más de cuatro años, la intervención gubernamental lo puso fin.

En Hoshana Rabba 1042, las dos partes llegaron a un acuerdo que estipulaba que Solomon ben Judah continuaría como gaon y Nathan ben Abraham sería el mejor jugador, pero bajo la estricta supervisión de los hijos del difunto gaon Solomon ha-Kohen, el "Cuarto" y "quinto" en la yeshiva. Tuvia ben Daniel continuó como "tercero". El acuerdo fue firmado por todos los miembros de la yeshiva, así como por los Karaite nesi’im, que se habían puesto del lado de Nathan ben Abraham. Aunque Nathan se convirtió en un apostador, murió tres años después y nunca se convirtió en gaon, mientras que Solomon ben Judah continuó ocupando el puesto durante muchos años.

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

1) Abu Isḥāq Ibrahim ibn al-Nag'hdīlah ibn Aṭā al-yahūdī '(Abraham Nagid born Kairouan abt 975)

1 “A history of Palestine, 634-1099, Volume 1” by Moshe Gil, CUP Archive, 1992 ISBN0521404371, 9780521404372

2. “Jews in Islamic countries in the Middle Ages” by Moshe Gil & David Strassler Translated byDavid Strassler, BRILL, ISBN900413882X, 9789004138827

3. Fragments from the Cairo Genizah in the Freer Collection (1927), 197-201

4. S. Assaf and L.A. Mayer, Sefer ha-Yishuv, 2 (1944), index; Shapira, in: Yerushalayim, 4 (1953), 118-22

5. “Egyptian Fragments. תולגמ, Scrolls Analogous to That of Purim, with an Appendix on the First םידיגנ” Author(s): A. Neubauer Source: The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Jul., 1896), pp. 541-561 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Historical note: The origin of the title of 'Nagid' in Egypt is obscure. Sambari and David ibn Abi Zimra (Frumkin, "Eben Shemuel," p. 18) connect it directly with a daughter of the Abbassid calif Al-Ṭa'i (974-991), who married the Egyptian calif 'Aḍud al-Daulah (977-982). But 'Aḍud was a Buwahid emir of Bagdad under Al-Muktafi; and, according to Ibn al-Athir ("Chronicles," viii. 521), it was 'Aḍud's daughter who married Al-Ṭa'i. Nor does Sambari give the name of the nagid sent from Bagdad. On the other hand, the Ahimaaz Chronicle gives to the Paltiel, who was brought by Al-Mu'izz to Egypt in 952, the title of "nagid" (al-Mu'izz lived from 932 until 975) (125, 26; 129, 9; 130, 4); and it is possible that the title originated with him, though the accounts about the general Jauhar may popularly have been transferred to him. If this be so, he was followed by his son, R. Samuel (Ahimaaz Chronicle, 130, 8), whose benefactions, especially to the Jews in the Holy Land, are noticed.

This must be the Samuel mentioned as head of the Jews many hundred years previous by Samuel ben David, and claimed as a Karaite. The claim is also made by Firkovitch, and his date is set at 1063. He is said to have obtained permission for the Jews to go about at night in the public streets, provided they had lanterns, and to purchase a burial-ground instead of burying their dead in their own courtyards (G. pp. 7, 61). The deed of conveyance of the Rabbinite synagogue at Fostat (1038), already referred to, mentions Abu Imran Musa ibn Ya'ḳub ibn Isḥaḳ al-Isra'ili as the nagid of that time. The next nagid mentioned is the physician Judah ben Josiah, a Davidite of Damascus, also in the eleventh century (S. 116, 20; 133, 10); a poem in honor of his acceptance of the office has been preserved (J. Q. R. viii. 566, ix. 360).

Nagid's authority at times, when Syria was a part of the Egyptian-Mohammedan empire, extended over Palestine; according to the Ahimaaz Chronicle (130, 5), even to the Mediterranean littoral on the west. In one document ("Kaufmann Gedenkbuch," p. 236) the word is used as synonymous with "padishah." The date is 1209; but the term may refer to the non-Jewish overlord. In Arabic works he is called "ra'is al-Yahud" (R. E. J. xxx. 9); though his connection with the "shaikh al-Yahud," mentioned in many documents, is not clear. Meshullam of Volterra says expressly that his jurisdiction extended over Karaites and Samaritans also; and this is confirmed by the official title of the nagid in the instrument of conveyance of the Fostat synagogue.

At times he had an official vice-nagid. To assist him he had a bet din of three persons (S. 133, 21)—though Meshullam mentions four judges and two scribes, and the number was at times increased even to seven—and there was a special prison over which he presided (M. V. p. 186). He had full power in civil and criminal affairs, and could impose fines and imprisonment at will (David ibn Abi Zimra, Responsa, ii., No. 622; M. V. ib.; O. p. 17). He appointed rabbis; and the congregation paid his salary, in addition to which he received certain fees. His special duties were to collect the taxes and to watch over the restrictions placed upon the further construction of synagogues (Shihab al-Din's "Ta'rif," cited in R. E. J. xxx. 10). Even theological questions regarding a pseudo-Messiah, for example—were referred to him (J. Q. R. v. 506, x. 140).

On Sabbath he was escorted in great pomp from his home to the synagogue, and brought back with similar ceremony in the afternoon (S. 116, 8). On Simḥat Torah he had to read the Pentateuch lesson and to translate it into Aramaic and Arabic. Upon his appointment by the calif his installation was effected with much pomp: runners went before him; and the royal proclamation was solemnly read (see E. N. Adler in J. Q. R. ix. 717).

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

Nota histórica: El origen del título de 'Nagid' en Egipto es oscuro. Sambari y David ibn Abi Zimra (Frumkin, "Eben Shemuel", p. 18) lo relacionan directamente con una hija del califa abasí Al-Ṭa'i (974-991), quien se casó con el calif egipcio 'Aḍud al-Daulah ( 977-982). Pero 'Aḍud era un emir Buwahid de Bagdad bajo Al-Muktafi; y, según Ibn al-Athir ("Crónicas", viii. 521), fue la hija de 'Aḍud quien se casó con Al-Ṭa'i. Tampoco Sambari da el nombre del nagid enviado desde Bagdad. Por otro lado, la Crónica Ahimaaz le da al Paltiel, quien fue llevado por Al-Mu'izz a Egipto en 952, el título de "nagid" (al-Mu'izz vivió desde 932 hasta 975) (125, 26; 129, 9; 130, 4); y es posible que el título se haya originado con él, aunque las cuentas sobre el general Jauhar pueden haber sido transferidas popularmente a él. Si esto es así, fue seguido por su hijo, R. Samuel (Ahimaaz Chronicle, 130, 8), cuyas bondades, especialmente a los judíos en Tierra Santa, se notan.

Este debe ser el Samuel mencionado como cabeza de los judíos muchos cientos de años antes por Samuel ben David, y reclamado como Karaita. Firkovitch también hace el reclamo, y su fecha se establece en 1063. Se dice que obtuvo permiso para que los judíos se desplazaran por la noche en las calles públicas, siempre que tuvieran linternas y compraran un cementerio en lugar de enterrando a sus muertos en sus propios patios (G. pp. 7, 61). La escritura de transporte de la sinagoga rabinita en Fostat (1038), ya mencionada, menciona a Abu Imran Musa ibn Ya'ḳub ibn Isḥaḳ al-Isra'ili como el nagid de esa época. La siguiente nágida mencionada es el médico Judá ben Josías, un Davidita de Damasco, también en el siglo XI (S. 116, 20; 133, 10); se ha conservado un poema en honor a su aceptación del cargo (J. Q. R. viii. 566, ix. 360).

La autoridad de Nagid a veces, cuando Siria era parte del imperio egipcio-mahometano, se extendía sobre Palestina; según la Crónica de Ahimaaz (130, 5), incluso al litoral mediterráneo en el oeste. En un documento ("Kaufmann Gedenkbuch," p. 236) la palabra se usa como sinónimo de "padishah". La fecha es 1209; pero el término puede referirse al señor supremo no judío. En las obras árabes se le llama "ra'is al-Yahud" (R. E. J. xxx. 9); aunque su conexión con el "shaikh al-Yahud", mencionado en muchos documentos, no está clara. Meshullam de Volterra dice expresamente que su jurisdicción se extendió sobre Karaitas y Samaritanos también; y esto lo confirma el título oficial de la nágida en el instrumento de transporte de la sinagoga Fostat.

A veces tenía un vice-nagid oficial. Para ayudarlo, tenía una apuesta de tres personas (S. 133, 21), aunque Meshullam menciona cuatro jueces y dos escribas, y el número a veces aumentó incluso a siete, y había una prisión especial sobre la cual él presidió ( MV pág. 186). Tenía pleno poder en asuntos civiles y penales, y podía imponer multas y encarcelamiento a voluntad (David ibn Abi Zimra, Responsa, ii., No. 622; M. V. ib .; O. p. 17). El nombró rabinos; y la congregación pagó su salario, además del cual recibió ciertos honorarios. Sus deberes especiales eran recaudar los impuestos y vigilar las restricciones impuestas a la construcción adicional de sinagogas ("Ta'rif" de Shihab al-Din, citado en R. E. J. xxx. 10). Incluso las preguntas teológicas con respecto a un pseudo-Mesías, por ejemplo, fueron remitidas a él (J. Q. R. v. 506, x. 140).

El sábado fue escoltado en gran pompa desde su casa hasta la sinagoga, y lo llevaron de vuelta con una ceremonia similar por la tarde (S. 116, 8). En Simḥat Torah tuvo que leer la lección del Pentateuco y traducirla al arameo y al árabe. Tras su nombramiento por el califa, su instalación se vio afectada con mucha pompa: los corredores fueron antes que él; y la proclamación real fue leída solemnemente (véase E. N. Adler en J. Q. R. ix. 717).

<---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->

read more

View All

Immediate Family

Text View

Showing 7 people

??? bat Mevorakh ben Eli

wife

Abu Isḥāq Ibrahim Sahl (abu I...

son

Abu ’l-Hasan ʿAlī ben al-Sh...

son

ʿAbd Allāh ben Muḥammad al-M...

son

David Avraham ben Hazub, Exilarc...

father

unknown

mother

Yehuda "Zakai" ben David, 29th E...

brother

____________________________________________________________________________