Max Lowenthal

Max Lowenthal | |

|---|---|

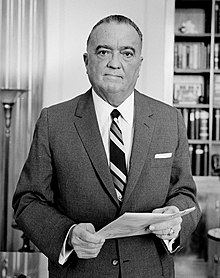

Max Lowenthal en su oficina de Washington (1939) | |

| Nació | Mordejai Lowenthal 26 de febrero de 1888 Minneapolis , Minnesota, Estados Unidos |

| Murió | 18 de mayo de 1971 (83 años) Nueva York , EE. UU. |

| Nacionalidad | americano |

| Educación | Universidad de Minnesota |

| alma mater | Escuela de leyes de Harvard |

| Ocupación | Abogado, consejero legal del gobierno |

| Años activos | 1923-1967 |

| Conocido por | Amistad con Harry S. Truman , tutoría de Carol Weiss King |

Trabajo notable | La Oficina Federal de Investigaciones (1950) (libro) |

| Niños | David Lowenthal , John Lowenthal y Elizabeth Lowenthal |

| Parientes | Julian Mack (tío de la esposa) |

| Familia | David Lowenthal y John Lowenthal (hijos) |

Max Lowenthal (1888-1971) fue una figura política de Washington, DC , en las tres ramas del gobierno federal en las décadas de 1930 y 1940, tiempo durante el cual estuvo estrechamente asociado con la carrera ascendente de Harry S. Truman ; sirvió bajo Oscar R. Ewing en un "grupo político no oficial" dentro de la administración Truman (1947-1952). [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8]

Antecedentes [ editar ]

Mordechai Lowenthal nació el 26 de febrero de 1888 en Minneapolis , Minnesota. En la década de 1870, sus padres Nathan (Nephtali) Lowenthal y Gertrude (Nahamah) Gitel, judíos ortodoxos, emigraron de Kovno (ahora Kaunas ), Lituania , a Minnesota. A una edad temprana, comenzó a usar el nombre más "estadounidense" de Max. Tenía dos hermanos mayores, de los cuales solo uno sobrevivió a la infancia. [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]

Se graduó de North High School en 1905, primero en su clase. También asistió al Talmud Torá , donde aprendió hebreo. Recibió una licenciatura en 1909 de la Universidad de Minnesota y se graduó en 1912 de la Facultad de Derecho de Harvard , donde comenzó una amistad de por vida con Felix Frankfurter . [1] [3] [4] [5] [6] [8]

Carrera [ editar ]

Se presume que muchos de los logros de Lowenthal se desconocen, ya que algunos se están descubriendo a través de la investigación histórica. Lowenthal tenía una personalidad increíblemente discreta y, a menudo, se negaba a atribuirse el mérito de sus logros. [ cita requerida ]

Un memorando en el archivo del FBI de Lowenthal revela la siguiente cronología (complementada [6] ):

- 1907-1909: Reportero en Minneapolis Journal

- 1912-1913: asistente legal del juez Julian Mack a 1.800 dólares anuales [6]

- 1913-1914: asistente legal de Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft (AKA Strong & Cadwalader [6] ) a $ 1.800 por año

- 1915: funda su propio bufete de abogados en la ciudad de Nueva York [6]

- 1917: Secretario o asistente en el Departamento de Estado de EE. UU.

- 1917-1918: subsecretario de la Comisión de Mediación del presidente estadounidense Woodrow Wilson (Misión Morgenthau, recomendada por Felix Frankfurter) [6] )

- 1918: ayuda informal en el Departamento de Guerra de EE. UU.

- 1918-1919: Vicepresidente de la Junta de Políticas Laborales de Guerra de Felix Frankfurter [6] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13]

- 1919-1920: regresa a la práctica privada; defiende a Sidney Hillman y a los trabajadores de la confección fusionados en un "caso histórico de orden judicial" [6]

- 1920-1921: Subsecretario del Congreso Industrial del Segundo Presidente

- 1920-1929: se asocia en el bufete de abogados Szold Branwen [sic] y se convierte en un "abogado de Nueva York muy adinerado" en Lowenthal, Szold y Brandwen [14] de 43 Exchange Place, Nueva York. [6] [7] [15] (El comisionado de la FTC, John J. Carson, más tarde recordó por error a un socio como "Max Bramblin" de "Lowenthal & Bramblin" [16] )

Lowenthal conocía a Walter Weyl (padre del miembro del Grupo Ware , Nathaniel Weyl ), quien recomendó a Adelaide Hasse como investigadora para la Junta de Políticas Laborales de Guerra . [12]

Práctica de derecho privado [ editar ]

Lowenthal dirigió una práctica de derecho privado desde 1912 hasta 1932. Los casos involucraban derechos de los trabajadores, defensa de la legislación sobre el derecho de huelga y derechos de los accionistas en casos de administración judicial. [6]

A principios de la década de 1920, Lowenthal parece haber tenido un despacho de abogados en la ciudad de Nueva York. Aunque Ann Fagan Ginger no lo menciona como mentor de Carol Weiss King en su biografía de King, Ginger sí dice que King formó una "sociedad flexible" con abogados radicales, que incluían a Joseph Brodsky , Swinburne Hale , Walter Nelles e Isaac Shorr. así como una asociación a largo plazo con Walter Pollak (una vez socio de Benjamin Cardozo , a quien conoció a través de su cuñado Carl Stern . [17] Sin embargo, los informes periodísticos de King (en la década de 1950) mencionan a Lowenthal no solo como un asociado sino como su empleador. [18] [19] El Saturday Evening Post fue aún más lejos en 1951 en un largo artículo sobre Carol Weiss King:

Otro protegido importante de Lowenthal (y su socio Robert Szold ) fue Benjamin V. Cohen , más tarde conocido como uno de los Hotdogs de Felix Frankfurter en el New Deal. Lowenthal y Cohen conocían al juez Julian W. Mack , quien era uno de los profesores de Cohen en Harvard (y era tío de la esposa de Lowenthal). En octubre de 1920, Cohen trabajó por primera vez para Lowenthal en un caso de quiebra que involucraba a EF Drew & Company . [21]

En 1923, Lowenthal fue consejero general de la Corporación Industrial Ruso-Estadounidense (RAIC) de 31 Union Square, Nueva York, fundada por el sindicato Amalgamated Clothing Workers en 1922, luego de una visita en 1921 a la Unión Soviética del presidente del sindicato Sidney Hillman . También fue uno de los directores originales del Amalgamated Bank of New York, como se anuncia en la revista Liberator . El anuncio menciona que el banco es propiedad y está operado por los Trabajadores de la Confección Amalgamados. Incluye al presidente Hyman Blumberg , al presidente RL Redheffer, al vicepresidente Jacob S. Potofsky , al cajero Leroy Peterson y a otros directores: Hillman, August Bellanca, Joseph Gold, Fiorello H. La Guardia , Abraham Miller , Joseph Schlossberg , Murray Weinstein , Max Zaritzky y Peter Monat . [22] La relación de Amalgamated parece haber comenzado con Lowenthal defendió a Hillman en 1920 en una disputa laboral en Rocherester, Nueva York. Todavía en 1929, Lowenthal todavía tenía una relación cercana con Amalgamated, ya que después de Wall Street Crash de 1929 recomendó que el banco vendiera sus valores por dinero en efectivo; a lo largo de la Gran Deparesión, el banco mantenía sus activos en efectivo o equivalentes de efectivo. "Fue el consejo de Max Lowenthal lo que ayudó más que cualquier otra cosa a mantener nuestros bancos abiertos durante el colapso bancario de Hoover", señaló Hillman más tarde. El asesor de Lowenthal en este período fue Benjamin V. Cohen. [21]

Servicio gubernamental [ editar ]

Durante sus primeros días en la política, Lowenthal se desempeñó como asesor de varios senadores de Estados Unidos. [ Cita requerida ] En 1929, se desempeñó como pro bono secretaria en presidente de Estados Unidos Herbert Hoover 's Comisión Nacional de Derecho observados y aplicados (más tarde llamada la Comisión Wickersham ) para investigar los crímenes relacionados con pandillas y la aplicación de la prohibición hasta julio de 1930, cuando renunció . [4] Ayudó a Ferdinand Pecora en las audiencias del comité del Senado que investigaban las causas del desplome de Wall Street de 1929 . Las audiencias lanzaron una importante reforma del sistema financiero estadounidense. [23] Alrededor de 1930, "otro trabajo que me asignaron en relación con la acusación de que en el gobierno había hombres que estaban tomando posiciones en el gobierno y que tenían inversiones privadas", se relacionó (que Lowenthal no contó claramente más tarde) con su amigo de la Facultad de Derecho de Harvard, el procurador de EE. UU. El general Charles Hughes, Jr. (1929-1930), hijo del 11º Presidente del Tribunal Supremo Charles Evans Hughes, Sr. En 1933-1934, fue consultor del Comité de Moneda y Banca del Senado de los Estados Unidos. "No recuerdo haber trabajado para ningún comité del Congreso antes de eso, pero no quisiera afirmar esto categóricamente". [1]

Reorganización ferroviaria [ editar ]

En 1933, Lowenthal comenzó a defender la reforma ferroviaria al volver a publicar su argumento original de Harvard Law Review The Railroad Reorganization Act en forma de libro junto con un segundo libro, The Investor Pays (1933) [24] [25] [26] [27] (Felix Frankfurter atribuyó gran parte del trabajo en The Investor Pays a Benjamin V. Cohen. [21] ) Los abusos que citó incluyeron: control de la administración judicial y de la reorganización por parte de los propietarios antes del reconocimiento de la insolvencia, administración inadecuada de las propiedades antes de la reorganización, supervisión regulatoria inadecuada, y conflictos de intereses. Mientras hacía rondas "como agentes del presidente" con Tommy Corcoran(uno de los "Happy Hotdogs" de Felix Frankfurter), Lowenthal le dijo a todos y cada uno que nada sucedería "sin la ayuda de la mano de obra ferroviaria". [8] El 5 de julio de 1935, el coordinador federal Joseph Bartlett Eastman escribió al senador Wheeler (presidente del comité), con Lowenthal como abogado del comité, para recomendar 18 ferrocarriles (incluidos Van Sweringen Lines , Pennsylvania Railroad , Wabash Railway y Delaware & Hudson Company ) además de financieros ( JP Morgan & Company y Kuhn, Loeb & Company ) para la investigación, como se informó en el New York Times y Railway Age . [28]Solo en diciembre de 1936 Lowenthal logró obtener suficiente documentación citada para comenzar la investigación real, según Railway Age . [29] En 1939, el Senado había introducido un "Lowenthal Bi | ll" para crear un "Tribunal de Reorganización Ferroviaria" especial para ferrocarriles en quiebra y reducción de capitalización y reducción de cargos fijos. [30] En abril de 1939, el comisionado de la CPI, Walter MW Splawn, y el abogado del comité Lowenthal testificaron. Lowenthal explicó los cambios en la nueva Ley de Reorganización de 1939 (aprobada y promulgada el 3 de abril de 1939). Su tribunal especial haría "reorganizaciones más sólidas" gracias a jueces capacitados en ferrocarriles. [31]

Truman [ editar ]

En 1935, Lowenthal se reunió con Harry S. Truman , después de que Truman se uniera a un subcomité del Comité de Comercio Interestatal del Senado de EE. UU., Investigando ferrocarriles y sociedades de cartera (que resultó en la Resolución 71 del Senado de EE. UU. El 4 de febrero de 1935. El senador Robert F. Wagner tuvo que retirarse del subcomité, y el senador Burton K. Wheeler ocupó su lugar con Truman. Los senadores en ese subcomité incluían: Wheeler (presidente), Truman, Alben Barkley , Victor Donahey , Wallace White y Henrik Shipstead . Los asesores legales de ese subcomité fueron Telford Taylor , asistido por Lowenthal y Sidney J. Kaplan(quien más tarde dirigió la División de Reclamaciones en la oficina del Procurador General del Departamento de Justicia de los Estados Unidos durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, [32] George Rosier , Lucien Hilmer y John Davis. [1] Según el secretario de nombramientos de Truman, Matthew J. Connelly , "Lowenthal se desempeñó como abogado del senador Truman durante las audiencias sobre el establecimiento de la Junta de Aeronáutica Civil". [33] Según su hija Margaret Truman , Truman confió en Lowenthal para mantener la presión sobre Missouri Pacific Railroad y Alleghany Corporation sobre el " Asunto del Pacífico de Alleghany-Missouri ". [34] [35]

Lowenthal recordó más tarde: "Hasta que entramos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial, es posible que haya estado haciendo algún trabajo para el Comité de Comercio Interestatal. Estuve durante varios años, en esa categoría que se conoce como hombres de un dólar al año, pero , cuando entramos en la guerra, tuve una charla con el senador Wheeler y le sugerí que probablemente debería estar disponible para algún trabajo de guerra, y el presidente Wheeler pensó que eso era correcto ". [1] Por lo tanto, Lowenthal no sirvió con Truman en el llamado " Comité Truman " (1941-1944) (formalmente, el Comité Especial del Senado para Investigar el Programa de Defensa Nacional, 1941-1948, desde 1948 el Subcomité Permanente de Investigaciones o "PSI", y el actual "Subcomité Permanente de Investigaciones de Seguridad Nacional del Senado de los Estados Unidos ")." Asistí a una o dos audiencias por interés, pero estaba completando el trabajo para el Comité de Comercio Interestatal en ese momento y luego participé en algún trabajo en el esfuerzo de guerra que fue bastante absorbente: era trabajo de día y de noche ", recordó más tarde. [1]

De 1944 a 1946, Lowenthal dejó el servicio oficial del gobierno. En 1944, Lowenthal asistió a la Convención Nacional Demócrata de 1944 en Chicago. En 1944, Truman le escribió a su hija que Lowenthal, William M. Boyle y Leslie Biffle "estaban tras mi pista ... Sí, están conspirando contra tu padre" junto con muchos otros "tratando de convertirlo en vicepresidente en contra de su voluntad. " [34] Truman le dijo a Lowenthal que FDR lo había incluido en su lista corta de candidatos a vicepresidente. Lowenthal fue con Truman a reunirse con Philip Murray , jefe del sindicato del Congreso de Organizaciones Industriales (CIO) en busca de apoyo. "Creo que alguien de su organización [36]había estado pidiendo otro nombre a Phil Murray, pero creo que con el tiempo se colocó detrás del Sr. Truman ". [1]

En el otoño de 1946, Lowenthal almorzó con Bob Patterson , recién ascendido de subsecretario de guerra a secretario de guerra , a quien conocía "desde hace muchos años": Patterson le dijo a Lowenthal que lo enviaría a Berlín para "un trabajo de guerra, o un tarea producida en tiempos de guerra ... Creo que fue el último cargo oficial que ocupé en el gobierno ". El trabajo consistía en restituir la propiedad robada por los nazis . Lowenthal informó al alto comisionado estadounidense de Alemania, general Lucius D. Clay . [1] [3] Específicamente, Lowenthal pasó seis semanas en Alemania para recopilar pruebas y poder redactar un informe. [5]

A su regreso a los Estados Unidos, Lowenthal "tenía mucho trabajo" en casos de propiedad "sin heredero" relacionados con los nazis. En ese período, el Fiscal General de los Estados Unidos ( Tom C. Clark en ese momento) hizo recomendaciones que incluían "relajar la prohibición universal de las escuchas telefónicas", momento en el que Lowenthal "notó que eso estaba en la lista". [1]

En 1948, Truman sintió (según Lowenthal en 1967) que el proyecto de ley Mundt-Nixon de ese año era "para castigar la sedición". [1]

Investigaciones del FBI y el HUAC [ editar ]

Durante 1947-1948, el FBI investigó a Lowenthal. Utilizaron escuchas telefónicas, como se evidencia en archivos del FBI editados posteriormente por la FOIA. Los archivos del FBI sobre Lowenthal también incluyen versiones preliminares de su libro de 1948 sobre el FBI. [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] [43]

En 1950, Lowenthal publicó un libro crítico de la Oficina Federal de Investigaciones (ver Obras, más abajo), que llevó a testimonios que negaban que había "ayudado e instigado" a los comunistas en el servicio gubernamental ante el Comité de Actividades Antiamericanas de la Cámara . El libro y la prensa negativa ayudaron a poner fin a una carrera de 38 años en el servicio público. [3]

El 28 de agosto de 1950, Lee Pressman testificó que había no recomendada Lowenthal para un trabajo en la Junta de Producción de Guerra . [7]

El 1 de septiembre de 1950, Charles Kramer se negó a responder preguntas sobre si conocía a Lowenthal. [7]

Ese mismo día, el representante de Estados Unidos, George A. Dondero, calificó a Lowenthal de "amenaza para los mejores intereses de Estados Unidos". Dondero dijo que su carrera en el gobierno estuvo "repleta de incidentes en los que ayudó e instigó a los comunistas" a partir de 1917. [44]

On September 15, 1950, Lowenthal appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee AKA "HUAC" (two of whose members were Mundt and Nixon–of the Mundt-Nixon Bill). Already in August 1950, HUAC had re-subpoenaed four witness who had been part of Whittaker Chambers's Ware Group: Lee Pressman, Nathan Witt, Charles Kramer and John Abt. The committee had asked both Pressman and Kramer whether they knew Lowenthal; both confirmed. Lowenthal brought former U.S. Senator Burton K. Wheeler as counsel. After reviewing his curriculum vitae, the committee tried to link him with known Communist Party members and organizations, some of which he confirmed, others not, all without admitting any wrongdoing. Names mentioned included: Alger Hiss, Donald Hiss, David Wahl, Bartley Crum, Martin Popper, Allan Rosenberg, Lee Pressman, the Russian-American Industrial Corporation, the Twentieth Century Fund, and the International Juridical Association.[7]

On November 19, 1950, the government published Lowenthal's closed-session testimony from September 15, 1950. During testimony, Lowenthal had denied aiding or abetting Communists in government service. Specifically, he denied any involvement in the employment or sponsoring of George Shaw Wheeler, a former US government employee who had defected to Czechoslovakia in 1947 and publicly requested political asylum there in 1950. He noted that Wheeler had been transferred to his division on the Board of Economic Warfare from the War Production Board "toward the end of my service with the board" He also said that Wheeler had not worked with him in Germany." He also claimed to have advised Lee Pressman in 1944 against naming Henry A. Wallace as Democratic candidate for vice president.[44]

On November 27, 1950, Senator Bourke B. Hickenlooper noted, "In the Washington Post of November 26, 1950, there are published two reviews of a recent book entitled The Federal Bureau of Investigation, by Max Lowenthal, New Deal mystery man of Washington." The first ("A Lawyer's Indictment in Mood of Prosecutor") was by Rev. Edmund A. Walsh S.J., of Georgetown University, which Hickenlooper read into the record. The second by Joseph L. Rauh Jr., a former civil servant, whom Hickenlooper denounced for criticizing the FBI, for chairing the National Committee for Democratic Action, and for affiliations with Alger Hiss, Donald Hiss, Felix Frankfurter, William Remington, and James L. Fly of Americans for Democratic Action. Hickenlooper stated "I have the greatest admiration and respect for the integrity of the director, Mr. J. Edgar Hoover, and his staff personnel" at the FBI.[45]

Unofficial policy group member[edit]

During the 1950s, Lowenthal supervised "an operation... conducted... to prepare answers to the charges that Senator McCarthy was making." This followed McCarthy's to the State Department of "a list." Lowenthal was later unable to recall clearly the names of anyone who helped him: Truman Library oral historian Jerry N. Hess suggested that they might have included Herbert N. Maletz, Lowell Mellett, and Franklin N. Parks. The White House was supportive: when Lowenthal came to Washington to work, sometimes he would get office space there.

In May 1951, White House Appointments Secretary Matthew J. Connelly asked Lowenthal to help General Harry H. Vaughan in "setting up testimony", after Vaughan admitted repeated episodes of trading access to the White House for expensive gifts.[46][47] Later, he also helped Connelly himself (who was convicted of bribery charges in 1956).[1] (When asked whether Lowenthal served on that counter-McCarthy committee, Connelly, however, said, "Not that I recall. He had nothing to do with the White House."[33])

In mid-summer 1951, Truman wrote Lowenthal to thank him for a letter and respond regarding Senator Joseph McCarthy's speech of Jun 14, 1951, attacking George Marshall. They discussed the need for the U.S. government to support international security. "I certainly did appreciate your good letter," Truman ended.[34]

In 1952, when Truman announced he would not seek re-election, Vice President Alben Barkley could not secure the presidential nomination from the Democratic Party due to a lack of endorsement from labor leaders. Connelly later recalled:

Lowenthal introduced Truman to U.S. Supreme Justice Louis Brandeis.[1]

In 1953, Lowenthal was "member" of the Truman Administration, according to the papers of American evangelist Billy James Hargis (who also lists him among "Alleged Reds" 1950–1954).[48]

Lowenthal's best known accomplishment occurred during his term as the chief adviser on Palestine to Clark Clifford, an advisor to President Truman, from 1947-1952.[citation needed] President Truman credited Lowenthal as being the primary force behind the United States recognition of Israel.[citation needed] (Apparently in contrast, Matthew J. Connelly pointed to David Niles, an associate of Harry Hopkins from the WPA), as "very effective in the problems we had in connection with the recognition of Israel" because of his contacts in the Jewish community: "David Dubinsky, Abraham Feinberg. You name any leader in the Jewish faction, and he had intimate contacts with him." Connelly denoted Lowenthal as one of contacts–"oh, very much so, very much so." When Niles died in 1951, Connelly chose Feinberg to succeed him in that liaison role.)[47]) Historian Michael J. Cohen argues that Clark Clifford relied on Lowenthal for advice on Israel, and Lowenthal in turn on Benjamin V. Cohen.[21]

In the late 1950s, Norman Thomas criticized Bertrand Russell for citing Lowenthal and Cedric Belfrage as authorities on wrongdoings by the FBI. Russell responded in "The State of Civil Liberties" in The New Leader, published on February 18, 1957. Russell retorted, "You seem to imply that criticisms of the FBI can be ignored if they come from Communists or Fellow-travellers. In particular, you point out that Mr. Lowenthal had a grievance against the FBI. It is, however, an almost invariable fact that protests against injustice originate with those who suffer from them." In which case, Russell recommended that Thomas go buy and read Lowenthal's book.[49]

As late as 1967, Lowenthal denied ever even discussing Israel with President Truman and claimed to have only heard of the partition of Palestine through a secondhand source in the White House.[citation needed]

Personal life and death[edit]

Lowenthal was married to Eleanor Mack, niece of Judge Julian Mack. They had three children: David (1923), John (1925) and Elizabeth (Betty).[6] His sons were David Lowenthal and John Lowenthal.[50]

On September 15, 1950, Lowenthal told HUAC that he kept homes at 467 West Central Park in Manhattan and in New Milford, Connecticut.[7] During World War II, he resided at 1 West Irving Street, Chevy Chase, Maryland.[51]

Regarding Truman overall, late in life Lowenthal told Truman Library oral historian Jerry N. Hess:

During the same interview, however, Lowenthal remembered Truman only one staff by name (Victor Messall).[1]

Regarding Truman's views on red scares in the United States, Lowenthal commented:

He died age 83 on May 18, 1971, at home (444 Central Park West) of heart ailment.[3][4][5]

Lowenthal was a trustee of the Twentieth Century Fund from 1924 to 1933.[7][52][53]

Recollections about him[edit]

Recollections of Lowenthal from Truman Library oral histories are mixed.

Some are favorable:

- "Disciple of Louis Brandeis": Margaret Truman[34]

- "A famous investigator" in 1935: Roswell L. Gilpatric, Deputy Secretary of Defense (1961–64)[54]

Others are less favorable:

- "(Truman said)... I have two Jewish assistants on my staff, Dave Niles and Max Lowenthal. Whenever I try to talk to them about Palestine they soon burst into tears because they are so emotionally involved in the subject" in 1948: : Oscar R. Ewing, organizer and member of unofficial political policy group during Truman administration (1947–52)[2]

- " I know they thought he was a Communist. And I never could figure that out. They came around to me about it. Max was a far-out liberal. He was a very good investigator on the railroads.": Raymond P. Brandt, St. Louis Post-Dispatch Washington Bureau Chief (1934–1961)[2]

Stephen J. Spingarn, Federal Trade Commission Commissioner (1950–1953), recalled,

However, Spingarn also suspected that Lowenthal (and Connelly) "stuck the knife in me." Phileo Nash told Spingarn it was Connelly, influenced by Lowenthal:

Spingarn further recalled:

After the FBI book came out, Westbrook Pegler, a right‐wing columnist, called Lowenthal "the mysterious New York lawyer, who now appears to have picked Harry Truman for President."[3]

In the early 1930s, claimed Whittaker Chambers in his 1952 memoir Witness, Lowenthal (Max "Loewenthal" in Witness) was a member of the International Juridical Association (IJA), along with Carol Weiss King, Abraham Isserman, and Lee Pressman.[58] In the inaugural issue of the Monthly Bulletin of the International Juridical Association (May 1932), "Max Lowenthal, member of the New York bar" appears in an article called "Protest Meeting."[59] During his 1950 HUAC testimony, Lowenthal admitted that he had helped organize the "National Lawyers Guild" in the 1930s. He was also a member of the American Bar Association and the New York Bar Association.[7]

Works[edit]

In 1950 he wrote a book about the FBI,[60][61] in which he dealt with issues he felt were still unresolved "although they were brought to light and discussed by statesmen in 1908 and 1909 when the police force now known as the FBI was created." The New York Times announced the book a day in advance of its publication on November 21, 1947, with a subtitle that read "Lawyer Says Hoover Policies Set Up Secret Police."[62] In New York Times Sunday Book Review, Cabell Phillips said the book showed "immense research and careful documentation" and "almost for the first time... it pulled aside the self‐righteous cloak in which the FBI has wrapped itself."[3] Writing for the University of Chicago Law Review in 1952, however, T. Henry Walnut (member of the Pennsylvania Bar) noted "From Mr. Lowenthal's review of the FBI's political activities they would appear negligible between the years 1924 and 1946, when the Bureau picked up the trail of the Communist. This period, however, was not a political vacuum. It was filled with differences as bitter as any the country has ever known... If Mr. Lowenthal is still looking for evidence as to what can be done through the FBI, under its present centralized direction from Washington, to oppress dissenting individuals and groups, it would be well for him to study the period from December 8, 1941 to the end of 1945.[63] George M. Elsey, Administrative Assistant to the President (1949–1951) felt that "Lowenthal had a passionate dislike of the FBI and J. Edgar Hoover in particular." Asked to read galley proofs for his book on the FBI, he later commented, "The book was so unfair, so grossly biased, so sloppily done in every respect that it couldn't possibly influence anybody about the FBI. Any serious reader would just lay the thing aside in disgust... The President was just tolerant, shrugged his shoulder, tended to laugh it off and say, 'Oh, Max is that way'."[64]

Books:

- The Investor Pays (1933)[65] (1936)[66]

- The Railroad Reorganization Act (1933)[67]

- Uncredited speeches for Harry S. Truman[68]

- The Federal Bureau of Investigation (1950)[69][70] (1971)[71]

- Police methods in crime detection and counter-espionage (1951) (paper)[72]

See also[edit]

- Felix Frankfurter

- Julian W. Mack

- Carol Weiss King

- Benjamin V. Cohen

- Sidney Hillman

- Harry S. Truman

- Oscar R. Ewing

- Robert Szold

- John Lowenthal

- David Lowenthal

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Lowenthal, Max; Hess, Jerry N. (1967). "Oral History Interview with Max Lowenthal". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Ewing, Oscar R.; Hess, Jerry N. (2 May 1969). "Oral History Interview with Oscar R. Ewing 4". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Max Lowenthal, Lawyer, Dies; Book on F.B.I. Stirred a Storm". New York Times. 19 May 1971. Retrieved 19 August2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Max Lowenthal. Papers, 1929-1931". Harvard Law School Library. February 2006. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Collection of Max Lowenthal (1945–1947)". EHRI Consortium. 4 April 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Max Lowenthal papers, 1910-1971". University of Minnesota. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hearings regarding communism in the United States Government: Hearings before the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-first Congress, second session. US Government Printing Office. 15 September 1950.

- ^ a b c Latham, Earl (1959). The Politics of Railroad Coordination 1933-1936. Harvard University Press. p. 19 (personal network), 26 (1933), 31 (Frankfurther), 256 (Corcoran), 265 (Corcoran). ISBN 9780674689510. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Business Digest, Volume 6. Cumulative Digest Corporation. 1919. p. 721. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ How the Government Handled Its Labor Problems During the War: Handbook of the Organizations Associated with the National Labor Administration; with Notes on Their Personnel, Functions and Policies. Bureau of Industrial Research. 1919. pp. 4 (Wilson, Frankfurter), 10–11 (creation, purpose, personnel, organization). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Hearings of the United States Congress - House Committee on Un-American Activities". US GPO. 1950. p. 2960. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b Black, Clare (31 August 2006). The New Woman as Librarian: The Career of Adelaide Hasse. Scarecrow Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 9781461673347. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Monthly Labor Review, Volume 7. US GPO. 1919. p. 23. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Adele D. Bramwen, Artist, 64, Is Dead". New York Times. 14 August 1964. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Max H. Lowenthal, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 29 August 1947

- ^ Carson, John J.; Hess, Jerry N. (8 November 1971). "Oral History Interview with John J. Carson". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Ginger, Ann Fagan (1993). Carol Weiss King, human rights lawyer, 1895-1952. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-285-8. LCCN 92040157.

- ^ "Barbs". Dixon Evening Telegraph. 13 February 1952. p. 4 (employer). Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Russian Communism". Town Talk. 21 May 1954. p. 6 (associate). Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Craig (17 February 1951). "The Communists's Dearest Friend". Saturday Evening Post. p. 92.

- ^ a b c d Lasser, Willam (1 October 2008). Benjamin V. Cohen: Architect of the New Deal. Yale University Press. p. 10 (Lowenthal, Mack, Frankfurter), 47 (Cohen as protege), 52 (Amalgamated), 62 (Szold), 66–70 (railroads), 293–294 (Israel). ISBN 978-0300128888. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Amalgamated Bank of New York (advertisement)" (PDF), The Liberator, May 1923, retrieved 20 August 2017

- ^ Moyers, Bill.: Pecora Part II?, "Bill Moyers Journal", Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- ^ Clay, Cassius M. (1940). "The Case for a Special Reorganization Court". Law and Contemporary Problems. Duke University: 455 (fn 24). Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Foster, Roger S. (1935). "Conflicting Ideals for Reorganization". Faculty Scholarship Series. Yale University Press: 928 (fn 10: best expression of need for reorganization). Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Lubben, Stephen J. (6 September 2004). "Railroad Receiverships and Modern Bankruptcy Theory". Cornell Law Review. Cornell University Press. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ McCullough, David (24 May 2011). David McCullough Library E-book Box Set: 1776, Brave Companions, The Great Bridge, John Adams, The Johnstown Flood, Mornings on Horseback, Path Between the Seas, Truman, The Course of Human Events. Cornell Law Review. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781451658255. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Baer, Christopher T. (1935). "A General Chronology of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company: Its Predecessors and Successors and Its Historical Context: 1935" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A General Chronology of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company: Its Predecessors and Successors and Its Historical Context: 1936" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ "Prospective Transport Legislation and Railway Net Earnings". Railway Age. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Company. 106: 761–763 (763 Lowenthal Bill). 1939. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ "Hearings Begun on Wheeler Rail Revamping Measure". Railway Age. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Company. 106: 779–782 (779–780, 782 Lowenthal). 6 May 1939. Retrieved 2 December2017.

- ^ "About Us". Maslon, LLP. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ a b c "Oral History Interviews with Matthew J. Connelly". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. 28 November 1967. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Truman, Margaret (1959). Harry S. Truman. Harper Collins. p. 106 (Alleghany), 167 (Brandeis), 521–522 (MacArthur). ISBN 9780380721122. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Truman, Margaret (1959). Harry Truman. New Word City. ISBN 9780380721122. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Since Lowenthal was a legal counselor, his counterparts attending such an important meeting could have started Murray's CIO general counselor Lee Pressman.

- ^ "Subject: Max Lowenthal, Part 1 of 7" (PDF). FBI. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Subject: Max Lowenthal, Part 2 of 7" (PDF). FBI. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Subject: Max Lowenthal, Part 3 of 7" (PDF). FBI. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Subject: Max Lowenthal, Part 4 of 7" (PDF). FBI. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Subject: Max Lowenthal, Part 5 of 7" (PDF). FBI. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Subject: Max Lowenthal, Part 6 of 7" (PDF). FBI. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Subject: Max Lowenthal, Part 7 of 7" (PDF). FBI. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Lowenthal Denies Any Ties to Reds". The New York times. 19 November 1950. p. 69.

- ^ Senate Congressional Record (PDF). US GPO. 27 November 1950. pp. 15780–15783, 15780 (book). Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "Harry H. Vaughan, Major General Who Was An Aide To Truman, Dies". New York Times. 22 May 1981.

- ^ a b "Oral History Interviews with Matthew J. Connelly". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. 30 November 1967. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Billy James Hargis Papers". University of Arkansas. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (12 October 2012). The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell Volume 29: Détente or Destruction, 1955-57. Routledge. pp. 163–164. ISBN 9781134245253. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Guide to the John Lowenthal Papers TAM.190". New York University. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ "Max Lowenthal: FOIA FBI Files, Part 7 of 7" (PDF). Milwaukee Road Archive. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Twentieth Century Fund: 1919–1994 (PDF). Twentieth Century Fund. 1994. p. 43. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ "Low Wages Are Discussed in Report: Study Is Made of the Relative Costs of Living at Home and in Foreign Countries"(PDF). Hammond Advertiser of Hammond, NY. 28 January 1932. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Gilpatric, Roswell L.; Hess, Jerry N. (19 January 1972). "Oral History Interview with Roswell Gilpatric". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Spingarn, Stephen J.; Hess, Jerry N. (21 March 1967). "Oral History Interview with Stephen J. Spingarn (2)". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Spingarn, Stephen J.; Hess, Jerry N. (29 March 1967). "Oral History Interview with Stephen J. Spingarn (8)". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Spingarn, Stephen J.; Hess, Jerry N. (20 March 1967). "Oral History Interview with Stephen J. Spingarn (1)". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 635fn (IJA). LCCN 52005149.

- ^ "Protest Meeting". Monthly Bulletin. International Juridical Association: 5. May 1932. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ The Federal Bureau of Investigation (William Sloane, pub. 1950)

- ^ The Federal Bureau of Investigation (Turnstile Press Limited, pub. 1950)

- ^ Hinton, Harold B. (20 November 1950). "Lowenthal Book Assails FBI: Lawyer Says Hoover Policies Set Up Secret Police". New York Times. p. 16. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ Walnut, T. Henry (1952). "The Federal Bureau of Investigation. By Max Lowenthal". University of Chicago Law Review: 638 (quote). Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Elsey, George M.; Hess, Jerry N. (10 July 1970). "Oral History Interview with George M. Else (9)". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Lowenthal, Max (1933). The investor pays. A. A. Knopf. LCCN 33014417.

- ^ Lowenthal, Max (1936). The investor pays. A. A. Knopf. LCCN 36014723.

- ^ Lowenthal, Max (1933). The Railroad Reorganization Act. Harvard Law Review Association. pp. 18–58. LCCN 41033437.

- ^ Daniels, Jonathan; Hess, Jerry N. (4–5 October 1963). "Oral History Interview with Jonathan Daniels". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Lowenthal, Max (1950). The Federal Bureau of Investigation. William Sloane Associates. pp. 559 pages. Retrieved 20 August2017.

- ^ Lowenthal, Max (1950). The Federal Bureau of Investigation. William Sloane Associates. pp. 559 pages. LCCN 50010837.

- ^ Lowenthal, Max (1971). The Federal Bureau of Investigation. Greenwood Press. pp. 559 pages. LCCN 50010837.

- ^ Lowenthal, Max (2 March 1951). Police methods in crime detection and counter-espionage. Conference on Criminal Law Enforcement. LCCN 51014347.

External sources[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Max Lowenthal. |

- "Max Lowenthal papers, 1910-1971". University of Minnesota. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "Max Lowenthal. Papers, 1929-1931". Harvard Law School Library. February 2006. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "Collection of Max Lowenthal (1945–1947)". EHRI Consortium. 4 April 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Truman Library - Max Lowenthal Papers

- Michael J. Cohen, Truman and Israel, (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990.)

- Ronald Radosh and Allis Radosh, A Safe Haven: Harry S. Truman and the Founding of Israel (HarperCollins, 2009)

- Library of Congress: Donald S Dawson papers, 1944-1993

- Library of Congress: Felix Frankfurter papers, 1846–1966

- Biblioteca del Congreso : Foto de Truman y Lowenthal (20 de octubre de 1937)

- Yad Vashem : Colección Max Lowenthal

- Colección EHRI de Max Lowenthal

- Universidad de Duke - caja de Max Lowenthal

- 1888 nacimientos

- 1971 muertes

- Abogados de Minneapolis

- Escritores de Minneapolis

- Alumnos de la Facultad de Derecho de Harvard

- Abogados judíos estadounidenses

- Personas asociadas con Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft

- Pueblo estadounidense de ascendencia judía lituana

- Socialistas judíos

- Abogados estadounidenses del siglo XX

- Alumnos de la Universidad de Minnesota

- La Fundación Century

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario